L'homme blanc et l'homme noir:

Othello in Les Enfants du paradis

Douglas M. Lanier

1 As all cinephiles know, Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert's Les Enfants du paradis is as quintessentially a French film as there is, one that consciously fashioned itself as a French classic from the start and that has consistently topped most surveys of the best French film ever made. What makes it intriguing is that for all the film's insistent, glorious francophilia, its climax occurs during a performance of Othello which comes at the end of a series of allusions, overt and implicit, to Shakespeare's play. Myriad critics have before spotted the allusions to Shakespeare's play and contextualized Frédérick Lemaître's performance within the history of nineteenth-century Shakespearean performance [1], but few have situated the film's use of Othello in the history of Shakespeare on screen or addressed its attitude toward Shakespeare. [2]

1 As all cinephiles know, Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert's Les Enfants du paradis is as quintessentially a French film as there is, one that consciously fashioned itself as a French classic from the start and that has consistently topped most surveys of the best French film ever made. What makes it intriguing is that for all the film's insistent, glorious francophilia, its climax occurs during a performance of Othello which comes at the end of a series of allusions, overt and implicit, to Shakespeare's play. Myriad critics have before spotted the allusions to Shakespeare's play and contextualized Frédérick Lemaître's performance within the history of nineteenth-century Shakespearean performance [1], but few have situated the film's use of Othello in the history of Shakespeare on screen or addressed its attitude toward Shakespeare. [2]

2 One important exception to this generalization is Russell Ganim. In an article entitled "Prévert reads Shakespeare," [3] Ganim focuses on the many ways in which Lacenaire and Iago are kindred characters ― both are 28 years old and of ambiguous sexuality, both look upon their peers with misanthropic disdain and believe their true value to be overlooked, both exude a calculating rationality that masks inner rage, both are masters of words and innuendo, both reveal (in Iago's case, "reveals") the sexual discretion of a superior's beloved, and both are playwrights of a sort, creating elaborate real-life "performances" that lead eventually to the death of their superior rival (Othello and Count Montray). Valuable as Ganim's analysis is ― and I recommend his article heartily ― at one level it does not go far enough, for, I want to observe, resonances, parallels, echoes and analogues of Othello suffuse Les Enfants du paradis, far beyond the few scenes in which the play is specifically referenced. [4] Garance, for example, corresponds in many ways to Desdemona, for both women are obscure, idolized objects of male desire that at some level the men cannot securely possess. Both women are wrongly accused of crimes in public and private (Garance twice so in the first half of the film), both unwittingly awaken jealousy in the men in their lives, and both end up with murderous husbands (or in the case of Garance, a murderous paramour). Baptiste himself observes that "one could make a nice pantomime out of Othello," and identifying with Othello's remorse in the final scene, goes on to observe that Shakespeare's tale of romantic self-destruction is "a sad and ridiculous tale, like so many others, like mine or yours, Madame Hermine" (193). [5] Baptiste's idealization of Garance, his investment in her as a means to redemption of his at first stigmatized identity as Anselme Deburau's denigrated son, and his potential for violent rage in service of his devotion to her, exemplified by his destruction of the outsize bouquet Count Montray gives Garance at the Funambules, a potential we see again in artistic form in his killing of the ragman in the pantomime Chand d'habits ― all of these suggest affinities between Baptiste's emotional sensibility and Othello's. In the film's second half Count Montray sneers at the indecorous barbarity of the Othello performance, but he too succumbs to the same impulse to jealousy that all the male protagonists at some point feel, though he conceals the barbarity of his emotions by channeling through gentlemanly ritual, challenging his rivals to duels. Ironically he is only in attendance at the Othello performance at all because he is convinced ― wrongly, like Othello ― that Frédérick, playing Othello, is the man Garance truly loves, a misconception he falls into when Garance doesn't give him the indication he wants that she is devoted exclusively to him. And he is killed in a Turkish bath, a setting which links him metaphorically with the "malignant and [...] turbaned Turk" (V.2.362) in Othello's final speech.

Even Nathalie, Baptiste's wife, plays out a combination of Emilia and Bianca's roles, pathetically pursuing a man who doesn't really love her, herself being so touched by jealousy at one point that she breaks the silence of the Chands d'habits pantomime and destroys its spell. And analogues with plot points and mise en scène from Othello also appear ― to take one example of each, Lacenaire's waiting for the authorities to arrive after he has killed the count, an act which will surely lead to his own execution, has some resemblance to Othello's self-immolating actions after Desdemona's murder. The curtained bed that has become iconic as the site of forbidden sexual desire and death in nineteenth-century performances of Othello appears several times in Les Enfants, most notably in Baptiste's room where it is the site of Garance's trysts with Frédérick and Baptiste. It is as if Othello has been disassembled ― narratively and thematically deterritorialized ― and become a freely circulating network of themes and motifs in which all the main characters of the film partake, a Shakespearean body without organs, a point to which I will return presently.

3 The film's first explicit reference to Othello seems to articulate in iconic language the poetic realist sensibility of Les Enfants. It comes from the lips of Frédérick, the character most consistently and explicitly associated with Shakespeare's play. He announces early in the film that he longs to be a famous, respected actor, and Othello becomes his vehicle for doing so.

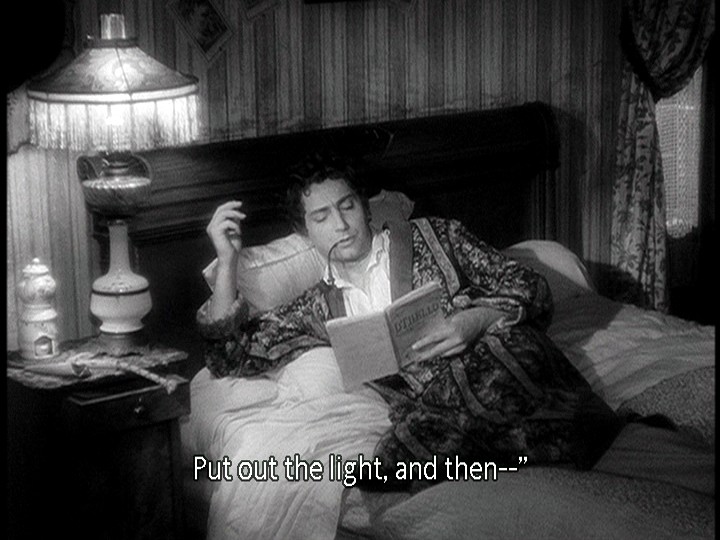

Lying in his bed in Madame Hermine's boarding house, Frédérick practices these lines from his script:

Yet I'll not shed her blood,

Nor scar that whiter skin of hers than snow,

And smooth as monumental alabaster.

Yet she must die, else she'll betray more men.

Put out the light, and then... (V.2.3-7)

This passage from Othello as he pauses before Desdemona's murder neatly captures the central psychological tension experienced by the men in the presence of the elusive Garance. On the one hand, they idealize and idolize her as Othello does Desdemona; Lacenaire speaks of her as his "guardian angel" and Baptiste associates her with magical, distant moonlight, so much that he cannot consummate their relationship when she offers herself to him. Indeed, Garance's role as the statue of Phoebe in Baptiste's pantomime L'Amoureux de la lune, where he adores her as Pierrot, literalizes Othello's image of the "monumental" virginal Desdemona he places on a pedestal, whom he adores but cannot bear to sully. On the other hand, Othello's jealous, violent desire to possess her for himself alone, his horror at her entertaining "more men," is one also shared by Garance's suitors, though it manifests itself in different ways. Othello's tortured oscillation between desire, even reverence for the idealized female object, his impulse to control that object, and his rage at her elusiveness are central to this passage and to a reading of Othello as tragic Romantic hero, brought low by his pursuit of a transcendent object he can never securely capture. It is not for nothing that in Garance's first appearance in the film, she is presented as the figure of Truth in a carnival sideshow. This quality, the film suggests, is the foundation of authentic art, art which speaks to the aspirations of the "children of paradise," the commons who inhabit the cheap seats, and it is this quality which Baptiste manages to express in his pantomimes and underlies his popularity. At this point in the film, however, Frédérick is incapable of feeling the sentiment he voices, for he views all women, Garance included, as objects of sexual pleasure, creatures to feed his narcissism. Frédérick's self-consciousness, his retreat from emotional involvement into self-regarding wit and exuberant charm, something he taps brilliantly in his send-up of L'Auberge des Adrets, manifests itself in his penchant for hammy acting, something he demonstrates here with his grandiose gestures and declamatory style. Indeed, Frédérick quips, "yes, let's turn out the light," and casually tosses the script aside, one of his signature gestures that marks his carefree lack of commitment, and almost immediately, intrigued by singing in the next room, he takes up his affair with Garance, engaging her with his characteristic witty repartee and casual erotic charm, the very antithesis of Baptiste's idealization and abandonment of Garance earlier in the evening. Frédérick's plotline consists of his development of sufficient emotional attachment to Garance to experience jealousy and thus to perform Othello with some authenticity.

4 In the film's first half, however, Frédérick remains trapped in narcissism, self-consciousness and verbal wit, a point made in the scene where backstage at the Funambules Garance and Frédérick discuss their faltering affair. As the scene opens, Garance speaks wistfully of her longing for a love that is silent or uses few words, precisely the kind of love Frédérick, even the easy talker, cannot offer.

After she declares that he must be unhappy with her because he can't resist joking, he replies with a dismissive speech about jealousy:

Perhaps you would like it ― I don't know, if I was always going on at you and asking questions, eh? If I made you tell me everything in your past, if I spied on you, watched you, followed you in the streets, from a distance, hugging the walls where I had written your name? If I woke suddenly in the middle of the night to demand who you were dreaming about? That, at least, would be absolutely useless.

Frédérick precedes this speech with tossing aside Garance's moon-goddess hairpin, another indication of his inability to idealize her enough to be jealous; for Frédérick, jealousy seems absurd, a cliche, a kind of emotional indulgence he refuses to engage in.

After revealing that she has already spoken Baptiste's name in her sleep, he invokes Othello:

What do you mean, that's all? Isn't it enough to reduce a heart like mine to despair? Do not forget, perfidious creature, that Othello killed Desdemona for much less than that. For nothing, do you hear? For nothing, Othello made himself a widower. For nothing, for a despicable little object, a mere handkerchief. A little batiste handkerchief, I'm sure! (104)

What is especially noteworthy about this speech is Frédérick's tone. Throughout much of it, he lapses into bemused histrionics, mocking the melodrama of "perfidious creature" by overacting it with a sweeping gesture. But at one point, on the line, "for nothing, Othello made himself a widower by his own hand" Frédérick fleetingly shows the capacity for genuine jealousy, awareness of the possibility for tragic immolation over a woman, the very antithesis of and a threat to his narcissism.

Almost immediately he pulls back from that sentiment, turning instead to a bad pun on "batiste mouchoir," a witticism he repeats with self-satisfaction, much to Garance's dismay. And as he exits there enters the man who will become his erotic rival, Count Montray, with his ridiculously ostentatious bouquet.

5 In the film's second half, Frédérick's meeting with Garance at the Funambules as the two watch Baptiste's Chand d'habits constitutes a crucial change for Frédérick. What we see of Frédérick's success ― the example the film gives is his travesty of L'Auberge des Adrets ― rests upon his quick wit and energy, performative self-awareness, and gift for puncturing authority and decorum. But exuberant though his performance is, it offers no artistic grandeur, precisely the quality that prompts Frédérick to see Baptiste's performance. Frédérick's exchange with Garance reveals something new, a retrospective recognition that Garance's attachment to Baptiste wounded his pride. As if replaying their earlier conversation Frédérick calls Garance "Desdemona," and he returns to the issue of jealousy:

I think I'm jealous. No, I don't know... I've never felt anything like it. It's heavy, it's unpleasant. It gets hold of you by the heart. The head wants to defend itself... and... hop! it's gone, with the rest of them! Do you hear, Garance..., there, just a moment ago, I was jealous, because of Baptiste, because of you... yes, I was jealous!... So, then, in one fell swoop, regrets flew in! That man, that traveler, who took you away, and I who let you go! And with it all, to make sense out of it all, Baptiste, who acts like a god! (164)

This time, however, Frédérick struggles to maintain composure, becoming uncharacteristically sincere and flooded by the pain of loss and envy, though he still experiences jealousy at something of a distance, speaking of it as if it were a separate entity assaulting him from outside. And his romantic jealousy remains bound up with professional jealousy, a recognition that Baptiste is the superior artist.

Talking about jealousy, he says, putting it at verbal arm's length ― this is Frédérick's characteristic psychological strategy ― robs jealousy of its power ― but when Garance suggests it was nothing more than a mild fit from which he's recovered, he takes exception:

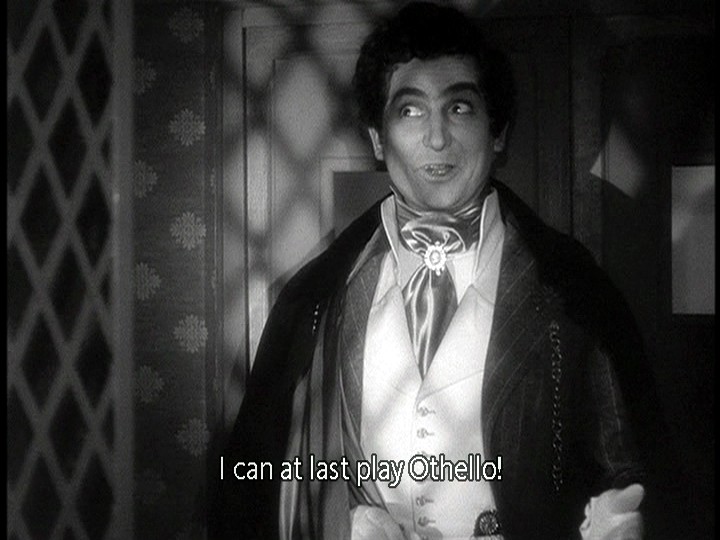

Cured! Why do you want me to be cured so quickly? And what if it pleased me, if it was useful to me to be jealous... useful, and even necessary! Thank you, Garance. Thanks to you, thanks to all of you, I shall be able to play Othello! I've been trying to find the character, but I didn't feel him. He was a stranger. There it is, now he's a friend, he's a brother. I know him... I have him in my grasp! Othello... the dream of my life... After you, Desdemona, of course, I shall clasp Baptiste to my heart, at least I owe him that, eh? (169)

Amidst the flash of fury at his wounded pride, here for the first time Frédérick recognizes the connection between emotional experience and artistic authenticity that grounds Baptiste's pantomimes, though we should also notice that even here Frédérick's experience of jealousy is oddly at a remove, useful for playing the part which is his heart's desire but not integral to his emotional being. Othello is "a friend... a brother," but not himself. And so at the end of the speech, we once again see the re-emergence of Frédérick's cynical histrionic side with his "After you, Desdemona," though it is underlaid with unsuspected love and regretful longing for Garance. The filming of Arletty in this sequence ― in ravishing closeups, veiled, in shadows ― establishes visually what Frédérick cannot quite say, that she has become for him an ungraspable object of desire in retrospect.

6 Without doubt, Frédérick's Othello performance constitutes his apotheosis as a stage actor. It has a psychological depth, intensity and grandeur we've not seen before, and an exchange of closeups between Garance and Frédérick at its climax underlines that its authenticity and power springs from his complex feelings for her.

What is more, as Frédérick's Othello speaks of murder, the camera pulls into Lacenaire's face, bearded like Frédérick's own in costume, suggesting an affinity between Othello's rage and Lacenaire's ― this moment, the camera seems to suggest, plants the idea for Lacenaire's revenge upon Count Montray. Montray himself, ever the spokesman for the arid, elitist taste of the classical theaters, finds the spectacle vulgar, a judgment which gives Frédérick's Shakespeare performance the frisson of popular rebellion and allies it with the working class spectators in the cheap seats, those known as les enfants du paradis. The irony is that the count's drive to own Garance, to discover and destroy his romantic rivals for her attention, only works to strangle off her spirit, a fact broadly hinted at from the count's very first entrance with what Baptiste waggishly calls a funeral bouquet. His attempt to insult Frédérick after the performance and goad him into a lover's duel spectacularly backfires, for Lacenaire, affronted by the count's imperious elitism and evident hypocrisy, casts the unwitting count in a real-life variation on the Othello scenario he so despises, what Lacenaire calls not a tragedy but a farce. In Othello the beloved's infidelity is entirely imagined, but here it is real and very public.

Drawing a curtain aside as if opening a play, Lacenaire reveals Baptiste and Garance embracing on the theater balcony. This climactic moment is Carné's nod to Romeo and Juliet, of course, a scene of star-cross'd lovers briefly consummating their deep, pure but ultimately doomed passions for each other, a balcony scene that "corrects" the earlier balcony scene between the ill-matched Garance and Frédérick which ended in their casual sexual dalliance, the very epitome of Frédérick's previous nonchalance. In many ways, this moment on the balcony is the film's primal scene, a scene recognized as such only after we've earlier seen its many adumbrations. [6] It is a moment that melds Othello's imagined scene of cuckoldry and public humiliation (as the count experiences it, a moment of triumph for the Iago-like Lacenaire) with Romeo's all-too-evanescent declaration of his love before tragedy descends (as Baptiste experiences it). It is equally a moment of artistic triumph for Frédérick. He channels his jealousy for Garance back into his acting and by so doing makes his art authentic, but he also uses his art to convert his Othello-like jealousy back into a Romeo-like declaration of love for Garance (this is the meaning of the bouquet he sends her during his performance). In his case, however, the triumph is primarily artistic, not erotic: he bests the count on the issue of Shakespearean theater, but in his final shot of the picture, he walks up the stairs alone, without Garance, still in blackface as Othello. It is Baptiste, the man in whiteface, who gets Garance and all she represents (French liberty, the truth of passion), albeit all too fleetingly.

7 There's more to say ― the film does not end with the balcony scene ― but what's notable about this network of Othello themes and motifs is that though persistent, they are what Edward Baron Turk has called "kaleidoscopic," diffuse, largely denarrativized, typically marked with a difference from Shakespeare. There are myriad resemblances between characters in Les Enfants and those in Othello, but those resemblances come in and out of view ― the characters of Les Enfants do not follow those of Shakespeare's play, and the full resonance of Othello really only comes into full view at Frédérick's performance. Even there, there are crucial differences that accord with the poetic realist sensibility of the film. Because the curtain falls at the moment of Desdemona's murder (on the portentous line "it is too late"), we never get Othello's remorse, his anagnorisis or his arguably tragically redemptive suicide. [7] This is quite different from Othello's assimilation into film mid-century in Anglo-American contexts, where, as in Les Enfants, Shakespeare's play is also often used to explore the fluid boundary between art and life. In Anglo-American popular film there is a strong tradition of the play Othello serving as an oppressive master-narrative that, once invoked, takes over the life of the person playing the Moor, drawing out jealousy and leading to real murder (or attempted murder) on the stage. [8]

Two films roughly contemporary with Les Enfants offer variations on this theme, Men are not Gods (UK, 1937) and A Double Life (USA, 1947). What both films (and others like them) capture is the extraordinary cultural authority of the Shakespearean text and plotlines in the Anglo-American sphere, though that authority is registered in perverse form, as a text which dredges up unconscious emotions and compels its players to act out its imaginary scenarios in real life. What makes Les Enfants's cinematic use of Othello distinctive (and perhaps distinctively French) is its dispersal of the Shakespeare narrative. When Othello proper finally appears at the end of the film, it seems like a momentary crystallization ― but by no means an authoritative or final one ― of themes and motifs of the narrative we've been watching all along. That narrative is constructed as a classic tale of French heritage, an articulation of a resolutely French history and set of values. Like Olivier's Henry V, another heritage film created in the shadow of World War II, Les Enfants reminds its audience of the national culture and history they were fighting to preserve. If, then, Les Enfants was self-consciously conceived in part as a French heritage classic, precisely the status it now holds, on a first viewing Othello seems curiously out of place in the film, particularly since it has been Hamlet, not Othello, that has been most influential as a model for modern French culture. But I want to suggest here that within the flow of the narrative of Les Enfants Othello seems to the viewer less like a master narrative, a source for the plot or characters, than an effect of this very self-consciously French story, a fleeting space of reterritorialization in the circulation of the particular kinds of unfulfilled desire and sumptuous mise en scène that marks these tales as French.

8 If we think of Othello as a product, not a source, of the Les Enfants narrative, then the ambivalence with which Shakespeare's play is deployed comes into clearer view. On one level, given Shakespeare's longstanding reputation as a chronicler of essential human nature, Carné and Prévert's evocation of Shakespeare is designed to indicate the universality of the film's themes, even as at the same time Shakespeare is shown to be essentially French in sensibility, at least in the case of Othello. At another level, however, Shakespeare is evoked as a paragon of spoken drama, the antithesis of classist classical French theater and thus potentially a theater of the people to rival the pantomime. It is important, then, to recall the note that Frédérick sends with his bouquet to Garance at his performance: "Desdemona has come this evening. Othello is no longer jealous. Othello is cured. Thank you" (196). The note reads in two ways, as a witty registration of Frédérick's erotic and artistic pride, in effect a return to his characteristic mode, but also as an acknowledgment of the cathartic nature of his performance. It is as much a purging of jealousy as it is a drawing upon it, another example of distancing through words, albeit fine words magnificently performed. By contrast, Baptiste's pantomimes, presented as a quintessentially French artform, distill, physicalize and heighten the underlying emotions ― they are not a means for purging so much as reliving and elevating them. Les Enfants lionizes the world of nineteenth century Parisian theater in all its manifestations, but its final alliance is with Baptiste and his art.

It is his art which is finally favored by les enfants du paradis, for after all the film's ironic final image is of a street ― by implication a nation ― filled with Pierrots. And, moreover, Baptiste's pantomime is also allied with silent film, the artform for which Carné was clearly nostalgic and which in the 1940s constituted France's great contribution to world cinematic culture. [9] The film's second half sharpens the contrast between theater and pantomime and makes clear that though Shakespeare's Othello may epitomize the best of the art of the dramatic word, the foundations of the cinematic future, the silent artform preferred by modern enfants du paradis, belonged not to the man in black but to the man in white, not l'homme noir but l'homme blanc. For all his virtues, like the Moor, Shakespeare himself remains ever the Other in the world of the film.

Notes

All Shakespeare references are from: Wells, Stanley, Gary Taylor, et al., eds. The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Second edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005 [1986].

1. For discussion of this history, see "Desdemona's Handkerchief." In John Premble. Shakespeare Comes to Paris. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2005. 93-117, as well as Robert Baldick. The Life and Times of Frédérick Lemaître. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1959. In Child of Paradise: Marcel Carné and the Golden Age of French Cinema. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1989, p. 261, Edward Baron Turk reminds us that the film is somewhat fanciful in its portrayal of Lemaître's triumphal performance of Othello, for "Othello was not one of the historical Lemaître's great roles, and by the mid-1830s he conceded that his talent was better suited to modern drama than to tragedy, be it Elizabethan or French Neoclassic." Turk suggests that Prévert chose to change this detail because Shakespeare provided a properly "lofty" counterweight to the commedia dell'arte elements of the film and Othello allowed Pierre Brasseur (who plays Lemaître) to showcase his acting prowess.

2. For example, in her excellent study of the film, Les Enfants du paradis. London: BFI, 1997, pp. 44-5, Jill Forbes notes, as many critics do, that the Romantics saw Shakespeare, and in particular Othello, as a means to reinvigorate French theatre, then under thrall of the Théâtre-Français. The references to Othello, she notes, thus have historical provenance and, more importantly, provide an important "touchstone not just for Frédérick's understanding of the relationship between Garance and Baptiste but for the emotional inspiration of his own art and that of the new theatre" (45). Nevertheless, when she turns to the issue of "theater as memory and repetition," she, like many critics, is far more interested in charting the resonances between Chands d'habits and Baptiste's pantomimes and the main plot than in the resonances of Othello.

3. Comparative Literature Studies, 38.1 (2001): 46-67.

4. Edward Baron Turk argues that Les Enfants "presents a world in which twin theatrical sources, the commedia dell'arte and Othello, thoroughly govern human relations. The film's kaleidoscopic succession of loves, jealousies, infidelities, and acts of vengeance transcend triviality to the degree that they are recognizable variants of established narrative patterns themselves represented in the film, namely, the parallel adventures of Pierrot, Colombina, Harlequin, and Pantalone... and Othello, Desdemona, Iago, and Brabantio" (Child of Paradise, p. 230). Though I agree with Turk that these narrative patterns serve to elevate the significance of the characters' emotions and actions, I would argue that the parallels to commedia function in quite a different fashion than do the parallels to Shakespeare's Othello, which are far more diffuse. William Hedges suggests that in the film's climactic scene, when Garance and Baptiste are discovered on the balcony after the performance of Othello, the situation pits commedia against Shakespeare, using the one to deflate or scramble the other. The count, for example, becomes in this scene "something like an Othello transformed into a tragic Pierrot" ("Classics Revisited: Reaching for the Moon." Film Quarterly 12.4 (Summer 1959): 33).

5. Children of Paradise: A Film by Marcel Carné. Trans. Dinah Brooke. NY: Simon and Schuster, 1968, p. 103. All citations from the film's dialogue are taken from this edition and are noted parenthetically.

6. Edward Baron Turk has perceptively and extensively discussed the film's many scenes of "unexpected discovery of a loved one's intimacy with another person" in terms of a recurrent Oedipal primal scene in Child of Paradise, pp. 302-24, though he has rather little to say about Othello.

7. Turk notes that such truncated endings were typical of nineteenth-century French versions of Shakespearean tragedy. However, I would not agree that the ending of Othello is truncated in the film in order to confirm Carné and Prévert's view "of Frédérick as incapable of emotional expansion" (Child of Paradise, p. 278).

8. For discussion of this motif, see Douglas M. Lanier, "Murdering Othello." The Blackwell Companion to Literature, Film and Adaptation. Ed. Deborah Cartmell. Blackwell: 2012. 198-215.

9. Similarly, Jean-Pierre Jeancolas observes that in Les Enfants "the cinema is paying homage to the theatre, to a theatre which is like its mirror: silent theatre, like silent film, loses nothing to the spoken word, even when that word is Shakespeare's. It is, among other things, an homage to the 'primitives' of theatre and of film" ("Beneath the Despair, the Show Goes on: Marcel Carné's Les Enfants du paradis." French Film: Texts and Contexts. Ed. Susan Hayward and Ginette Vincendeau. London: Routledge, 2000. 86).

How to cite

LANIER, Douglas M. "L'Homme blanc et l'homme noir: Othello in Les Enfants du paradis." In Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia (2010-). In Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin & Patricia Dorval (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/analysis/analysis_homme_blanc/ (last modified March 25, 2013).

Contributed by Douglas M. LANIER

<< back to top >>