Colour and Horror: Claude Barma’s 1973 Romeo and Juliet

Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin

Fig. 1. Dominique Paturel as Chorus. Opening sequence

1 “Vérone, Vérone la belle va être notre champ clos” (“Verona, fair Verona is going to be our battleground”): here are the opening words of Claude Barma’s 1973 television adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, [1] delivered by the darkly-clad Chorus (Fig. 1), played by a famous French actor and voice, Dominique Paturel. [2] Shakespeare’s text is adapted by Marcel Jullian, a prolific scriptwriter for French film and television. [3] The use of the expression “champ clos” points to the non-realistic décor of the film (Fig. 2) which ominously looks like a vault and constitutes a stifling background to the story, proper to feed a meaningful form of claustrophobia. It also points to the violence and conflict that are at the heart of Romeo and Juliet, the phrase “champ clos” referring to a place enclosed by fences where tournaments were held. Barma wanted to show the violence of the story. [4] The purpose of this short paper is to introduce this French “champ clos” adaptation of Romeo and Juliet by first briefly exploring its Zeffirellian aspects, by then showing how it combines contrary features that make it both a burning and freezing adaptation of Shakespeare’s play which echoed a woeful real-life story that had taken place in France in 1969 which was still in Claude Barma’s mind in 1973.

Fig. 2 The main décor of Claude Barma’s TV film

I. Claude Barma’s colour Shakespeare: Zeffirellian influences

2 Roméo et Juliette was broadcast on French television at 8:35 in the evening, as the opening of the traditional end of year TV festival, on the 21st of December 1973 on the second channel. [5] Before directing Romeo and Juliet, Claude Barma, who recurrently adapted literary works, had adapted Macbeth (1959), [6] Twelfth Night (La Nuit des Rois, 1962) [7] and Othello (1962) [8], all in black and white. Roméo et Juliette is his last Shakespeare and is in colour. After a series of black and white Shakespearean TV films broadcast at the beginning of French television, [9] Claude Barma uses the resources of colour to put the tragedy on screen, giving his version a Zeffirellian aspect. Indeed, Zeffirelli’s much acclaimed 1968 film remains memorable for its use of vivid colours and especially its colourful costumes. [10] Claude Barma’s film seems to be influenced by this meaningful use of colour.

3 The conflict between the two households is conveyed through a symbolic use of colourful costumes. Thus, the sequence which choreographs the first brawling episode (Fig. 3) between the Capulets and the Montagues conveys the confrontation between Tybalt and Benvolio through a contrast in colours.

Fig. 3. Tybalt (Gérard Ismael) versus Benvolio (Jean Louis Broust): a battle of colours

4 While at the beginning of the sequence the costumes do not say who is who, as if the two households were mirroring each other (Fig. 4), the camera then isolates Tybalt and Benvolio and suggests both their similarity and contrast through the colours of their costumes. The young generation on both sides wear bright colours while the Old Capulet and Montague wear darker, less vivid colours (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. The “thumb-biting” scene: the mirror effect between the two camps

Fig. 5. The Old Capulets’ (Jacques Eyser and Claude Genia) autumn colours

5 The resources of colour are also shown in the way the film emphasizes the presence of flowers. The first image that is associated with Romeo is a close shot of a rose (Fig. 6) which is evocative of Rosaline’s lover, announces Juliet’s balcony monologue (II.2.43-44) but which also, from the start, conjures up the carpe diem motif. We hear Romeo’s first words in a voice off when the rose is on screen.

Fig. 6. The first image that is related to Romeo

6 Then the spectators discover him talking with Benvolio, languidly lying among golden sheets surrounded by candles, another intimation of mortality, in an image that looks like a vanity (Fig. 7). The sequence is suggestive of a potential homo-erotic relationship between the two men.

Fig. 7. Romeo (Jean-Louis Broust) and Benvolio (Alain Liebolt)

Fig. 8. Romeo as Rosalind’s lover

Fig. 9. Romeo (Jean-Louis Broust) talking to Benvolio (Alain Liebolt)

7 The flower motif associated with a Prince-charming-like Romeo (Fig. 8-9), is evocative of a fragile youth, and is prolonged in the garden sequence that Barma imagines for the first dialogue between Old Capulet and Paris (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Old Capulet (Jacques Eyser) and Paris (Gil de Lesparda) in a garden sequence

8 Barma wanted to emphasize the youth of the characters by choosing two very young actors. Like Zeffirelli, he chose a young, 17-year-old, inexperienced actress to play the part of Juliet (Nathalie Juvet). Barma auditioned a hundred actresses to eventually choose a beginner. [11] Jean-Louis Broust, playing Romeo, had already played the part of Édouard III in Barma’s famous TV series, Les Rois maudits (1972), but was still a 21-year-old actor, whose relative inexperience would have been striking compared with the famous, more experienced actors playing the parts of the Prince, an impressive Georges Marchal (Fig. 11), or of Friar Laurence, the bewitching-voiced Jean Topard (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11. Georges Marchal as Prince Escalus

Fig. 12. Jean Topard as Friar Laurence

9 Colour is again used to suggest the burning vividness of youth in the ball sequence (Fig. 13-16).

Fig. 13. The ball sequence, before Romeo sees Juliet

Fig. 14. Juliet (Nathalie Juvet), watched by Romeo

Fig. 15. Romeo seeing Juliet

10 Romeo and Juliet are associated to become a couple of birds wearing the same feathers through the use of costume.

Fig. 16. No sooner meeting than kissing

11 The marketplace sequence with the nurse (Fig. 17) as well as the central tragic combat (Fig. 18) again cultivate the use of vivid colours to suggest the burning life of youth.

Fig. 17. Playing with the nurse in the marketplace

Fig. 18. Mercutio is killed under Romeo’s arm

After Tybalt’s death, the colours get darker to emphasize the gloomy side of the story that the spectators had already been made aware of from the start in several ways.

II. Burning and freezing: a Draculean atmosphere

12 The presence of the burning colours of youth that we have just described goes together with recurrent signs of death from the very beginning. The film opens with ominous storming sounds before we discover the dark chorus. The décor, which looks like a vault, is suggestive of mortality, and the recurrent presence of candles, as we have already noted, points to a realm of Vanities. Seeming to endorse Shakespeare’s cultivation of oxymorons in the play, Barma manages to combine the burning presence of youth and the freezing presence of death in several key “cold fire” or “sick health” (I.1.78) sequences. Before the ball scene, Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech is delivered in a dark mode, with the other characters around, including Romeo, striking by their immobility while hearing the Mercutio’s famous words (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. Romeo’s immobility during Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech

13 The film uses this kind of theatrical freeze frame on several occasions later, to create a chilling atmosphere, served by a clever use of Georges Delerue’s music, at the heart of a warm and lively sequence. Barma uses the same device in the ball sequence first to freeze the whole ball, including Juliet, when Romeo arrives, and then when all the characters appear at a standstill sitting around Romeo and Juliet who are thus the only living and dancing couple left in the ball. The couple is surrounded by these ghostly figures who seem to announce their death (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. Romeo and Juliet dancing among the vampires

14 The ball scene is thus turned into a kind of “dance of the vampires” sequence with all the ghostly figures around announcing their promised end. Barma embeds the love scene in a Halloween atmosphere through a freezing device which counterpoints the lovers’ burning feelings. The soundtrack enhances this ominous aspect as we hear distant and ironic voices strangely repeating the names of the two households, ‘Capulet”, “Montague” in the background of the lovers’ dance scene. We are never allowed to forget the ghostly presence of the family feud.

15 The tragic duelling scene also shows this freezing device to isolate Tybalt and Mercutio while all the other characters are at a standstill, in a theatrical and choreographed way before getting back to fighting (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. Mercutio (Marc Chapiteau) and Tybalt (Gérard Ismael) in the choreographed duelling scene.

The freezing device

16 The film plays on bawdy language and does not hesitate to emphasize the body of the lovers. The balcony scene does not enhance verticality and separation, as Romeo just quickly escalades a wall and then the two lovers are free to embrace for the whole scene. Juliet’s monologue (“Wherefore art thou Romeo?”, II.2.33ff) is directly delivered to Romeo, up to the phrase “prends-moi” [“take all myself”], the scene leaving no space for any eavesdropping moment. This directness again appears in the bedchamber sequence when we discover Romeo and Juliet, naked, barely hidden by the veil of their four-poster bed (Fig. 22-23).

Fig. 22. Romeo and Juliet in bed

Fig. 23. Romeo and Juliet in bed in close-up

17 The farewell scene is also put under the sign of bodily display as Juliet leaves her bed naked, to try and keep Romeo a little longer. It is the nurse who prudishly covers her body a few seconds later (Fig. 24-25).

Fig. 24. Farewell scene. The last embrace

Fig. 25. The nurse covering Juliet’s naked body

One can feel the liberated sexual atmosphere of the 70s in this sequence but also the limit it had to have on television on that familial New Year festival occasion.

18 The bed is later thrown into relief in the sequence staging Juliet’s mock suicide. The decaying body that is at the heart of Juliet’s fears, is visually emphasized when her monologue is replaced by an interpolated ghost sequence. Before she drinks the Friar’s potion, Juliet fearfully sees the ghost of her cousin Tybalt (Fig. 26), attracting her into the vault he’s now inhabiting.

Fig. 26. Juliet's terror when she sees the ghost of Tybalt

19 Barma uses another Halloween-flavoured episode by staging a vampire-like Tybalt who shows and describes the horrible things Juliet will see once she has joined him (Fig. 27).

Fig. 26. Juliet’s terror when she sees the ghost of Tybalt

20 The sequence is clearly evocative of the horror film aesthetics that should give the spectators goose pumps. The words uttered by Tybalt’s ghost translate the horrible visions described by Juliet in IV.3:

Shall I not, then, be stifled in the vault,

To whose foul mouth no healthsome air breathes in,

And there die strangled ere my Romeo comes?

Or if I live, is it not very like

The horrible conceit of death and night,

Together with the terror of the place,

As in a vault, an ancient receptacle,

Where for this many hundred years the bones

Of all my buried ancestors are packed,

Where bloody Tybalt, yet but green in earth,

Lies festering in his shroud, where, as they say,

At some hours in the night spirits resort –

Alack, alack, is it not like that I,

So early waking, what with loathsome smells,

And shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth,

That living mortals, hearing them, run mad –

O, if I wake, shall I not be distraught,

Environed with all these hideous fears,

And madly play with my forefathers’ joints,

And pluck the mangled Tybalt from his shroud

And, in this rage, with some great kinsman’s bone,

As with a club, dash out my desperate brains?

O, look, methinks I see my cousin's ghost

Seeking out Romeo, that did spit his body

Upon a rapier’s point. Stay, Tybalt, stay!

Romeo, Romeo, Romeo, here’s drink. I drink to thee.(Romeo and Juliet, IV.3.33-58) [12]

21 These words are turned into an interpolated sequence which should produce terror in Juliet and the audience. Juliet first hears Friar Laurence’s bewitching voice, repeating and transforming some of the words he had uttered in IV.1: “Poison, gel, sommeil éternel, froide, seule, seule. Abandonnée dans l’ancien caveau où reposent les Capulet, seule, seule.” [“poison, frost, eternal sleep, cold, alone, alone. Abandoned in the ancient vault where the Capulets rest. Alone, alone”]. This is followed by a devilish laughter and Tybalt appears on screen, holding a cup and addressing Juliet (Fig. 28-30): “Seule, Juliette? Non. Non, je suis là, moi. Et les autres aussi. Les moisis, les pourris, les desséchés, les gluants. Tu sens comme nous puons? Bois, bois” [“Alone, Juliet? No, you’re not, I am here with you. And all the others too. The mouldy, the rotten, the dried ones, the slimy ones”].

Fig. 28. The skulls in the Capulets’ vault

Fig. 29. Tybalt’s ghost showing the “mouldy ones”

22 Then he drinks before addressing Juliet again: “Tu vois cette poussière? Ce sont les os de tes ancêtres ensevelis depuis des centaines d’années. Leurs esprits te frôlent, te touchent. Comme elles sont loin les mains tièdes de Roméo sur ton corps. Bois! Bois!” [“Do you see that dust? Here are your ancestors’ bones that have been buried for hundreds of years. Their spirits are close to you; they touch you. How far are Romeo’s warm hands on your body now! Drink! Drink!”].

Fig. 30. Tybalt’s sarcastic smile

23 Then Tybalt throws the blood-like liquid on the lens of the camera (Fig. 31), giving the whole sequence a nightmarish atmosphere that is evocative of the tradition of Dracula films.

Fig. 31. The camera lens smeared with a blood-like potion

The image of the blood dissolves into a shot of Juliet’s screaming face (Fig. 32).

Fig. 32. Juliet’s terror at the sight of Tybalt’s Draculean behaviour

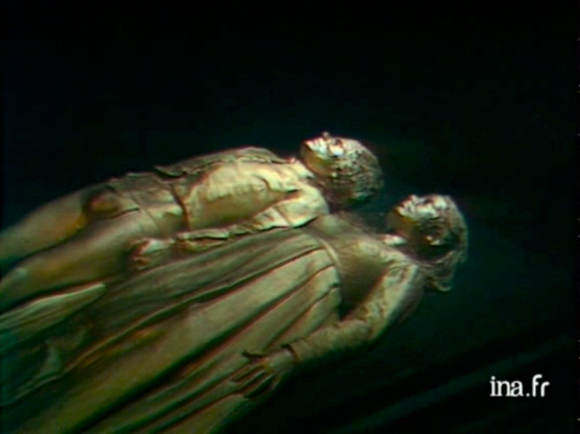

24 The tension between burning and freezing is epitomized in the last images of the film, which show Romeo and Juliet turned into golden statues (Fig. 33).

Fig. 33. Two statues “in pure gold” (V.3.299)

25 This final image is preceded by shots of a whole community powerlessly attending the disaster while listening to Friar Laurence’s explanations (Fig. 34).

Fig. 34. Last living tableau

This image of a society causing and then watching a catastrophe had a specific topical resonance in 1973.

III. “Mourir d’aimer”: the presence of a real-life story

26 In an interview published in Télé 7 jours, Claude Barma draws a parallel between the story of Romeo and Juliet and a contemporary one:

J’ai voulu montrer que l’amour de ces très jeunes gens était un amour complet, charnel. C’est au bout du compte une œuvre païenne où les personnages ne connaissent pas le péché originel. […] Aujourd’hui encore on peut mourir d’amour […] Gabrielle Russier n’est-elle pas morte par amour?

[I wanted to show that the love of these very young people was a complete, carnal form of love. At the end of the day it is a pagan piece of art in which the characters don’t know the original sin. […] One can still die of love nowadays. Hasn’t Gabrielle Russier died of love?] [13]

27 The journalist describes the association as incongruous (“jugement étrange: jamais Juliette n’a voulu mourir d’amour” (“what a strange remark: Juliet has never wished to die of love”) and yet Barma’s parallel tells a lot about the trace that this real-life forbidden love story left in the memories. Claude Barma is indeed referring to the woeful love story of Gabrielle Russier, a 32-year-old teacher, and Christian Rossi, a 16-year-old student, which had made the headlines in 1969. The teacher, who had been accused of corruption of a minor (the age of majority being 21 at the time) and sentenced to jail, committed suicide. The story had caused a lot of emotion and had even become a national issue on which President George Pompidou had been questioned. [14] A few years later, Annie Girardot played the part of the teacher in André Cayatte’s 1971 adaptation of this news item entitled Mourir d’aimer, [15] which was a box office success, watched by 6 million spectators and had some posterity, notably thanks to Charles Aznavour’s original soundtrack, especially the song entitled “Mourir d’aimer”. [16] The story was re-adapted, on TV this time, in 2009, with Muriel Robin in the leading role. No doubt that the forbidden love story was still in the spectators’ minds when they saw Barma’s Roméo et Juliette, Shakespeare’s story thus mirroring the debate on law and passion that took place in 1969.

28 Barma’s Roméo et Juliette, although it is still very theatrical and can be considered as part of the French dramatiques, reveals choices that reflect the cinema of his time, notably through its Zeffirellian influences and Draculean aesthetics. It also reflects the spirit of a time which had known the sexual revolution after May ’68 but was also haunted by the requests of decorum and put legal limits to the expression of passion. Colour and horror, fascination and repulsion go hand in hand in this version which constantly seems to suggest that the story of Romeo and Juliet is all about mourir d’aimer.

Notes

1. The film is available on the website of the INA (Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, Inathèque). See https://www.ina.fr/video/CPF86651356 (accessed 20 June 2021).

2. Dominique Paturel will later be known for his dubbing of J. R. in Dallas.

3. At the time Marcel Jullian had already become well-known for writing the scripts of the extremely popular French comedies: Le Corniaud (1964), La Grande vadrouille (1966) and La Folie des grandeurs (1971).

4. See Télé 7 Jours, Friday 21 December 1973, p. 92, accessible at http://php88.free.fr/bdff/image_film.php?ID=7127 (accessed 20 June 2021): “Claude Barma a voulu introduire une certaine violence, peu fréquente à la télévision” (“Claude Barma wanted to introduce a certain violence, that is not frequent on television”).

5. See the article entitled “Shakespeare ouvre le Bal.” Online: http://php88.free.fr/bdff/film/0021/13.jpg (accessed 1 July 2019).

6. On Barma’s Macbeth, see Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. “Le Macbeth de Claude Barma (1959): Shakespeare et l’expérience hybride de la ‘dramatique’.” In Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/analysis/analysis_macbeth_barma/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

7. On Shakespeare’s comedies on French television, see Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. “Remembrance of Things Past: Shakespeare’s Comedies on French Television.” In Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen: Television Shakespeare. Essays in honour of Michèle Willems. Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2008. 171-97. Also available in Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/hatchuel_vienne_2008/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

8. On Barma’s Othello, see Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. “‘O monstrous:’ Claude Barma’s French 1962 TV Othello.” In Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 3. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2014. Online: http://www.shakscreen.org/analysis/barma_othello/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

9. On Shakespeare at the beginning of French television, see Vincent Amiel. “Shakespeare et le début de la télévision française.” In Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/amiel_2013/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

10. To have an idea of this, see the film’s trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MPFYdqqL0vc (accessed 20 June 2021).

11. See Télé 7 Jours, Friday 21 December 1973, p. 92.

12. Romeo and Juliet. Ed. René Weis. Third Series. The Arden Edition, 2012.

13. Télé 7 jours, p. 92. See http://php88.free.fr/bdff/film/0021/19.jpg (accessed 20 June 2021).

14. See his interview at https://www.ina.fr/video/I00016723/georges-pompidou-sur-l-affaire-russier-cite-eluard-video.html (accessed 20 June 2021).

15. See a trailer at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIbhHiUaIug (accessed 20 June 2021).

16. See a montage of the song and pictures from the film at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LJPWSMoByOE (accessed 20 June 2021).

Filmography

Roméo et Juliette. Dir. Claude Barma. 1973. Available on the website of INA (Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, Inathèque): https://www.ina.fr/video/CPF86651356.

Bibliography

- AMIEL, Vincent. “Shakespeare et le début de la télévision française.” In Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/amiel_2013/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

- HATCHUEL, Sarah and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. “‘O monstrous:’ Claude Barma’s French 1962 TV Othello.” In Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 3. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2014. Online: http://www.shakscreen.org/analysis/barma_othello/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

- ―, “Le Macbeth de Claude Barma (1959): Shakespeare et l’expérience hybride de la ‘dramatique’.” In Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/analysis/analysis_macbeth_barma/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

- ―, “Remembrance of Things Past: Shakespeare’s Comedies on French Television.” In Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen: Television Shakespeare. Essays in honour of Michèle Willems. Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2008. 171-97. Also available in Patricia Dorval and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 2. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2013. Online: http://shakscreen.org/hatchuel_vienne_2008/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

How to cite

VIENNE-GUERRIN, Nathalie. "Colour and Horror: Claude Barma’s 1973 Romeo and Juliet." In Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 5. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2021. Online: http://shakscreen.org/analysis/vienne-guerrin_2021/.

Contributed by Nathalie VIENNE-GUERRIN

<< back to top >>