The Crimson Curtain (1952) in the Mirror of A Double Life (1947):

The Film noir Tradition (Plot, Characters, Setting)

Patricia Dorval

1 André Barsacq’s Le Rideau rouge (internationally known as The Crimson Curtain) – co-scripted with Jean Anouilh, and featuring Michel Simon, Pierre Brasseur and Monelle Valentin – was first shown on the silver screen in November 1952 in the wake of a pure film noir tradition production, A Double Life, by US director George Cukor – starring Ronald Colman and Signe Hasso – released on one side of the Atlantic in December 1947 and on the other some six months later (August 1948) as Othello. Interestingly, both works are quite atypical in the directors’ careers: multiple-award-winning [1] A Double Life is Cukor’s only excursion in the film noir style while A Crimson Curtain is theatre-bred Barsacq’s sole attempt at filmmaking.

2 Both footages basically revolve around inserting within a film a stage rehearsal/performance of a Shakespearean play. Understandably, a tragedy, from one of the masters of the genre, serves as groundwork for both classical film noir period creations, on the one hand Othello, on the other Macbeth. The two metatheatrically embedded constructions rest upon the grim identification of the main film protagonist with the theatrical character he impersonates on stage. The reflective double structure of film and stage performance in both A Double Life and The Crimson Curtain places them in the type of cinematic adaptation which Kenneth S. Rothwell terms “mirror movies”. [2] Although I have found no trace of any critical material to this effect, I am quite convinced that scriptwriters André Barsacq and Jean Anouilh viewed Cukor’s film, and that his metatheatrical embedding of a Shakespearean tragedy and drawing on film noir motifs served as source material for their own creation. Rather than dwelling on metatheatrical composition and other related interrogations on film, theatre and filmed theatre semiotics, showing how the inner and outer narratives interreact in both materials, I shall shift my focus on how the two films mirror each other in the way they rely upon film noir aesthetics. I would advise to read first the summary of the two movies at the end of this study in order to get a better grasp of the specifics of both.

3 Shot in black and white in the late 40s and early 50s, at the very heart of the film noir era, both films share a number of typical noir thematic and visual codes. Referenced in Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward’s encyclopedia of American film noir, [3] A Double Life is definitely a noir hallmark, which has received close, although not extensive, attention from film and/or Shakespearean scholars. [4] As to Barsacq’s Crimson Curtain, it is largely unknown and I have been unable to locate any criticism at all on this yet most stimulating production. Do both films rely on the same noir themes and cinematic features, and do they handle them in the same way?

I. Plot

4 Although, understandably, individual works may present specific features and not fit into normative categories, classic film noir academic critics have identified major noir-type plots. At the core of film noir is crime, often motivated by greed or jealousy, calling for an investigation by a police detective, a private eye, or sometimes even an amateur. Betrayals, double-crosses are prominent. False suspicions and false accusations are rife. Paul Arthur argues that the “living and the dead commingle in noir as in no other Hollywood product before or since.” [5] He further states that “[i]n addition to myriad tokens of the symbolic death of the subject – from near-fatal injuries to rhetorically inflated declarations of living death to prominent tropes of amnesia, dream sequences, and other markers of lapsed consciousness – protagonists assume the literal identities of dead men in nearly fifteen percent of all noir, including such disparate story constructions as Detours and T-Men. Dialogue referring to living characters as metaphorically ‘dead’ is nearly ubiquitous,” by which the author refers to voice-over constructions.

5 In line with major noir themes, both Cukor’s and Barsacq’s intrigues hinge on the perpetration of a sleazy homicide: in a death kiss, [6] Tony throttles the Brita-as-Desdemona-like waitress while Ludovic shoots Bertal-as-Banquo. Yet, the murder is handled in a drastically different way. Structurally speaking, although the two narratives have a fairly comparable length (103 minutes for A Double Life and 82 minutes for the Gaumont version of The Crimson Curtain – 90 minutes for the René Chateau one), the treatment of time differs dramatically. Cukor’s plot stretches at length over a period of some three years, starting with the on-going performance of a comedy by Robert E. Sherwood, A Gentleman’s Gentleman, through the rehearsal of the Othello production, through its two-year run to the tragic night of Tony/Othello’s death(s). Barsacq, for his part, squeezes his narrative into one single night, from a late afternoon rehearsal of Duncan’s murder scene (II.2) to the end of the performance, when the two criminals are apprehended. Two miles-apart time schemes which thoroughly shift the focus of the material: whereas Cukor lingers over his protagonist’s slow mental disintegration as the role of Othello poisons his mind with jealousy to the point of murder, Barsacq informs us, by scraps of dialogue mostly, of the predicament the couple has been in for years. As the film begins, they are psychologically ripe to take action. Consequently, in Cukor, the whole film runs towards and culminates, near the end, with the murder of Pat Kroll, before the camera. But Barsacq, who makes the crime the starting point of his narrative, in the first twenty minutes of the footage, keeps it offscreen and arranges for two characters to be suspectable. It follows that the place the spectator is put in and his experience are downright opposite in the two films. Although we pretty much know about “who dun it”, the question being rather, how?

6 Follows a crime investigation. In A Double Life, the inquiry is initiated by an amateur, press agent Bill Friend. Secretly in love with Brita, Bill becomes suspicious of Tony when a journalist happens to connect the way the waitress was murdered and the manner of Desdemona’s onstage death. The following day, the very front page of a local newspaper article (fig. 1) nicknames the real-life murder the “Othello murder”, interweaving metatheatricality and reality (01.19.58).

Fig. 1. The real-life Othello murder [7]

7 When Tony sees the headlines, he goes to the press agent and makes a scene that ends up in a fight during which Tony, as in a trance, tries to strangle Bill. As the latter’s suspicions gain ground, he calls him a maniac, and goes to the police station to share his concern. But the police have already arrested a suspect who has made a clean breast of it. The police detective confides that they too had a hunch about Tony at first but that he had an alibi, having spent the night at his ex-wife’s house. However, during a meeting with Brita, Bill learns that she and Tony quarrelled the previous night, and that he left and wandered by himself as he often does before coming back and sleeping on the couch. It then occurs to Bill that Tony’s alibi does not hold up. Shortly after, while Bill is having a drink at a bar counter, he is absorbed in the photograph of the dead waitress and her putative murderer in the newspaper. As he looks up and his gaze falls on a blond waitress resembling the victim, he has an idea, and – as Hamlet did to “catch the conscience of the king” (II.2.634) – he straightaway resolves to set Tony a mousetrap for him to show his guilt. After a few auditions, he hires an actress on account of her likeness with the waitress, has her clothed like her and has her wear a blond wig and the earrings found on the dead body. He then invites Tony to Frank’s bar and phones police detective Captain Bonner, asking him over to witness the scene. When Tony hears the Pat-like actress ask for their order, he raises his eyes to her, notices how much like his victim she looks, recognizes Pat’s earrings, and becomes quite disturbed. The startling fracas of glasses smashing on the floor behind him finishes off jarring his nerves, and he dashes out of doors. But the police officer does not consider Tony’s reaction evidence enough. The two men decide to go down to the Venezia Café, where Pat Kroll used to work and where Tony first made her acquaintance, for more information. The owner recognizes Tony on a photograph he is shown and remembers that he made a date with Pat. The detective admits that they are now getting close. The three men go over to the theatre for the witness to formally identify Tony. The ongoing performance has reached the last Act. And as Tony/Othello become(s) aware of the men’s presence just off the stage behind a Moresque fretwork door, it is actually to the audience he makes his farewell, not to the play’s characters (V.2.340-44). Just like Othello, he then lovingly makes his adieux to Brita/Desdemona and, like the Shakespearean protagonist, stabs himself to death – with a real dagger. In Cukor, the investigation taken on by an amateur – shadowed, as it were, by a skeptical traditional police detective – is pushed back into the closing ten minutes of the film, and basically ensures that the criminal is eventually punished to abide the moral guidelines of the Production Code of the time. But the moral code is diverted and the crime is atoned for by Tony taking his own life.

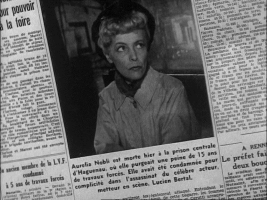

8 Barsacq chooses quite a different strategy. In the René Chateau version, The Crimson Curtain opens with a short rehearsal of the scene following the murder of King Duncan, a murder which happens offstage in the Shakespearean play, just as Bertal’s assassination occurs but a few steps away from the stage boards, in his dressing-room. The crime is committed at eight fifty-two by the clock just before the night performance, twenty-three minutes into the film and the police arrive shortly after to invest and seal off the theatre. From then on they will keep interacting with the personnel and nosing around for information. More unusual is the Assistant Inspector’s almost continuous presence at the edge of the stage so thrilled is he by his first experience of theatre. He follows the whole performance like a backstage spectator and it is he who unwittingly establishes a connection between the play and the murder they are looking into. His curiosity piqued by his colleague’s words, the chief inspector in his turn posts himself in the space between stage and backstage, not knowing which side he should investigate. From facing throughout the performance, scene after scene, Bertal’s ghost-like understudy as Banquo, played by the same Michel Simon, Ludovic becomes more and more distraught. Finally, in the Banquet scene, when Banquo’s ghost comes back from the dead (III.4), Ludovic has to face Bertal yet one more time, killed twice (once offstage and once onstage as Banquo) and coming back to life a second time, like some Lernaean Hydra. Endeavouring desperately to throttle him, Ludovic’s words are no longer Macbeth’s but his own which will commit him to prison. It follows that the whole metatheatrical performance is viewed through the gaze of the police who condition our interpretation. Barsacq plays at letting us on about who might wish to get rid of Bertal, but then deprives us of further information and we find ourselves walking in the steps of the police as they blunder about in their inquiries until they finally resolve the case. The two films therefore adopt a fundamentally different approach as to the place and function of the police and the spectator. This is not true of the Gaumont edit which introduces at the beginning a newspaper column (fig. 2) – clearly echoing A Double Life, but with a variation – telling of Aurélia Nobli’s death in prison, which serves to trigger the narration and flashback of the story three years after the facts. Thus giving the spectators all the information from the outset.

Fig. 2. News of Aurélia’s death in prison

9 Both productions rely on the doppelgänger device – a noir staple best found in Hollow Triumph (1948), directed by Steve Sekely with photography by film noir icon John Alton, which revolves around an educated gangster who finds his exact look-alike in a famous psychoanalyst, played by the same Paul Henreid, whom he will murder and impersonate. Although not so well known, Roses are Red, released the year before (1947) and directed by James Tinling, plays on the same trick, featuring a paroled convict who bears a striking resemblance with the local District Attorney, whose character and appearance he will assume, with the same Don Castle in both parts. [8] In both Cukor and Barsacq, the doppelgänger works as mirror – as much as play within in the case of A Double Life – to catch the conscience of the murderers. [9] As briefly described above, the press agent sets up a playlet alongside the main play within, which it seems to double, but for the fact that it is performed in a bar. He casts an actress in the role of the dead waitress who looks so much alike that she seems to Tony a ghost of the woman he has choked, which unnerves him completely. By so doing he gives himself away – even though this is not evidence enough for the police. This involves three look-alike characters: Brita as Desdemona in a blonde wig – the blond waitress Pat Kroll – the nameless actress playing the part of the waitress. Barsacq, on the other hand, chooses a different path for exploring the doppelgänger motif. [10] Bertal was to play Banquo in the tragedy, but as he is shot within minutes of the curtain rise, his understudy is summoned. And who should he be, but the dead ringer of the old man, played by the same actor, Michel Simon. Going through the performance, Ludovic/Macbeth will have to face what to him will look like a phantom of his victim; he will have to have it killed a second time under his very eyes as Banquo in III.3 (an interpolated element in the film), [11] and see it yet again rise from the dead in the banquet scene as the ghost of Banquo (III.4), whom he will try again to do in on the stage. Barsacq/Anouilh’s plot is more daring, if slightly unconvincing at the beginning, but so far-reaching.

10 Outside the main play within, both films introduce meta-theatricality in the form of playlets set offstage along with the main Shakespearean piece. In the case of A Double Life, it is simply the mousetrap essential to the investigation set up by the press agent. But Barsacq seems to enjoy sprinkling about tiny-weeny dramatic pieces although these are by no means instrumental to the plot. They mostly revolve around an old washed-up actor, Sigurd, who has been pestering the stage director (Bertal) for years for even a small part, but all he gets is spiteful insults. So eager is he to play that the least occasion prompts him to embark on tirades from previous parts in the most bombastic way, providing comic relief. Right after his latest squabble with Bertal, he meets a stagehand, vents his frustration to him, and brags that he will bump the old bastard off. As the young man laughs it off, Sigurd protests that he has talent and that he should have seen him as César de Bazan in Victor Hugo’s Ruy Blas, and he starts ranting the lines, “Gardez votre secret, et gardez votre argent. ǀ Oh! Je comprends qu’on vole, et qu’on tue, et qu’on pille, ǀ Que par une nuit noire, on force une bastille. ǀ D’assaut, la hache au poing–” (I.2) (time code 10.37-10.55). Some time later, he turns the bistro round the corner into a stage, declaiming Flambeau’s lines from Edmond Rostand’s L’Aiglon (II.8): “Et nous, les petits, les obscurs, les sans-grade, ǀ Nous qui marchions blessés, fourbus, crottés, malades, ǀ Sans espoir de duchés ni de dotations, ǀ Nous qui marchions toujours mais jamais n’avancions; ǀ Trop simples et trop gueux pour que l’espoir nous berne ǀ De ce fameux bâton qu’on a dans sa giberne” (time code 14.36-15.21). And once he has confided to the crime, and the chief inspector wants to know the details, instead of answering the questions he sets about miming the scene, repeating his words and gestures to dead Bertal’s body still on the floor (time code 55.20-56.45). Finally, as the inspector asks if he has any regrets, the actor explains with as much grandiloquence as before that he has played Don Diègue and several Roman actors in various tragedies, and that he regrets nothing. Now that his life is over, as is Bertal’s, and that, like Augustus in Corneille’s Cinna, he forgives him (Bertal), “Prends un siège, Cinna, prends, et sur toute chose…” (V.1.1), but as in the previous cases he is immediately rebuked and cut short. [12]

11 If the doppelgänger and metadramatric devices are crucial to pinning the culprits, both investigations first blunder along blind alleys, leading to false suspicions and accusations that are frequent in noir. In Cukor, the film spectator is told a poor slob living across the hall from the waitress has taken the rap. Although he says he was drunk and does not remember the details, he reportedly owns up to the crime, and the case is considered as closed. Likewise, in The Crimson Curtain, old Sigurd, in his cups on the night of the crime, is arrested shortly after the police arrive. Unlike Cukor’s production where the fall guy is neither seen nor heard, Barsacq’s character is fully fleshed out. He is the down-and-out type who finds refuge in alcohol, and as such is the ideal suspect: he both has the motive (Bertal has given him the hook and has kept telling him he is no good) and murder weapon (an old gun which he brandishes threateningly before a stagehand), and to top it all off he trumpets loudly and widely that he will kill the man. Although he has but muddled memories of what actually happened, Sigurd too confesses to the crime. The chief police inspector looks forward to an early night, but this is not counting his assistant’s naive concern with the play’s plot.

12 The two films’ denouements are definitely bleak, even tragic. Like his character in the play, Tony smites the turbaned Turk in him. Substituting (we never see when) a real dagger to the fake stage prop – as does Hieronimo in the play-within-the-play of Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy [13] – he stabs himself to death onstage in a climax of authenticity which crowns his career as an actor. On the other hand, the conclusion of The Crimson Curtain is better described as bleak. Barsacq’s characters do not suffer the fates of their dramatic personae. Aurélia does not slide into deadly madness as her role does, nor does Ludovic die. Both will serve life-sentence in prison, although the Gaumont version tells of Aurélia’s death after only three years of hard labour. Nothing more is said about Ludovic.

II. Character types and motivations

13 Flawed, morally questionable, alienated, “filled with existential bitterness:” [14] these words frequently describe noir protagonists. Among them are “hardboiled detectives, femmes fatales, corrupt policemen, jealous husbands, intrepid claims adjusters, and down-and-out writers.” [15]

14 Although none of our film protagonists qualifies as morally depraved, their character is definitely flawed, which will be their doom. Tony is unable to let go of his compulsive love for Brita whom he has indulged to divorce him but keeps urging to marry him again. Although he is not jealous at first, this peculiar situation will provide the ground for the seeds of jealousy to grow in, once sown by his performing of the Othello part. Moreover Tony’s psychological balance is not firm enough for him to be able to keep his own life and his theatrical roles apart, all the more so as he considers a good actor must make his personage’s words his own, his personage’s thoughts his own (27.00), yet in the same time considering it a fight to keep each in his place: “the battle begins: imagination against reality – keep each in its place – that’s the job, if you can do it” (28.22). So precarious is the balance between these opposite drives – making somebody’s thoughts one’s own and yet keeping them out – that Tony will fail to maintain such tenuous equilibrium. As the Broadway production runs night after night for weeks, months, even years, Othello’s sickly jealousy takes hold of Tony’s mind until he too wishes to put out his (ex) wife’s life lest she “betray more men.” He very nearly does so during a performance when tightening his grip around Brita’s throat too much despite her desperate, strangled appeals and the personnel’s hushed urges from just outside a door pulled just an inch ajar at the back of the set – even though in an attempt at playing it down, Brita will simply say that they overdid it a bit. Towards the end of the film, she will confide to Bill: “There is sometimes an emotional illness that comes over him” (01.17.41). As for Barsacq’s ménage à trois, it is singularly unwholesome. More will be said about it below.

15 Another major failing in the characters is addiction to drugs and alcohol, which scholars have identified as a usual film noir component “derived from the literature of drugs and alcohol.” [16] Hardly present in A Double Life – but for the verbal mention of the drunk falsely accused of the waitress’s murder – drugs and alcohol are quite prominent in Barsacq. As aforementioned, Sigurd’s frustration has led him to take to the bottle. He is another noir type, the embittered down-and-out actor derived from the “down-on-his-luck screenwriter” [17] and “has-been actress” [18] of Sunset Boulevard (dir. Billy Wilder, 1950), kindly turned into ridicule by Barsacq. On the night of the murder, he is so resentful and so intoxicated (fig. 3) – spurred on by Ludovic who keeps filling in his glass to inveigle him into killing the old man in his place – that he will own up to a crime he has not committed. On that very night, sickened with Bertal, Ludovic too indulges in too much drinking when he should keep his mind clear for the performance that is about to start (fig. 3). The essential point in Barsacq is that Ludovic is kept under Bertal’s thumb because he provides him with the drug he has become addicted to. And although the couple did try to break away, they had to come back because of Ludovic’s addiction. Drugs are therefore the reason for the threesome to be drawn to one another. But the character that fits the film noir archetype best is definitely Bertal even though he becomes the victim of his own maliciousness. Badly addicted, he is the only character actually seen shooting up (fig. 4). With his rugged face and manners, his harsh and rasping voice, his gruff intonations, his colloquial, slangy vernacular, his cynicism and callousness (one character says he was consumed with hatred), [19] and his total absence of moral values, he is the hard-boiled type. So morally depraved is he that he forces Aurélia to keep sleeping with him every night, so one of the actors says, only to smear her and her love relation with Ludovic. He furthermore wallows in his dirty innuendoes to the couple that they would be so better off but for him, but that Ludovic is too much of a coward to do anything, until he brings upon himself his own destruction.

Fig. 3. Ludovic and Sigurd drinking Fig. 4. Bertal preparing himself a fix

16 Jealousy is the driving force of the two plots. In Cukor, Tony shares with his role the same jealousy towards a man (Bill Friend) whom he suspects of having an affair with his (ex-)wife Brita/Desdemona. The fact that Tony and Brita have been married only to divorce and keep nibbling at the idea of getting back together again, makes the psychological issue more vivid. But he will not take the life of his adversary, he will have that of his wife. In the French film, the triangular relation is not fantasized, it is real, and it is the lover who will get rid of the cumbersome husband, but not without his wife’s encouragement. Reflecting the play, Aurélia is the first to take Bertal’s cue that they should imagine when playing that it is him they have just killed, and to bring up the idea of Bertal’s death. The Chief Inspector’s comment that he does not know what it was that stuck them three together [20] conveys the idea that the characters are inextricably linked in spite of themselves into an unbearably squalid situation.

17 Critics have established that film noir was more focused on psychological exposition than on crime solving. This is very much the case in Cukor where the investigation is run rather thin. This is mostly due, as suggested earlier, to the film stretching over a couple of years, the time for the character’s psyche to undergo fundamental changes. But, in Barsacq’s story which unravels over one single night, the characters’ psychological disintegration leading to the crime is less developed. What is developed is their mental collapse after the murder, which makes it part of the investigation. “In the postwar period,” Foster Hirsch argues, “many thrillers were about neurotic characters lured into a world of crime; victims and good men gone wrong, they are not hardened criminals […]. Rather they are often middle-class family men; steady, likeable fellows who happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, tricked by a twist of fate, seduced by the promise of sex or the chance to make quick illegal money.” [21] But as film noir developed, its characters’ psychologies became more extreme. [22] This is mostly true of Tony: likeable, yes; steady, not quite. And he and Brita know it, which is why she does not want him to accept the part of Othello, while he himself wavers, attracted to the wonderful role as much as cringing from it. The character will become unhinged and disintegrate into his play role. He will keep hearing an internal voice speaking to him, just like dead Bertal’s words that at times echo in Ludovic’s mind. Tony will repeatedly be jarred by the exacerbated and distorted sounds of glass or a train rumbling past. In both films, the characters’ minds are drawn to the verge of madness although Cukor exploits this element much more fully.

18 An interesting feature is that both Tony and Ludovic are reluctant to kill. As mentioned before, Tony one night nearly strangles Brita-as-Desdemona during the last scene of Othello, but then remorsefully swears to himself he will never hurt her. Later, after a violent quarrel once more motivated by jealousy, he might have done some mischief had not Brita run to her room and locked herself up. But instead he goes through the maze-like streets to Pat Kroll’s place and kills her in a death kiss motivated by her likeness with Brita-as-Desdemona. Pat Kroll becomes Brita’s substitute and the murder is displaced. As to Ludovic, he pounces upon the opportunity offered by Sigurd’s determination to kill Bertal and deviously spurs him on, expecting to have old Bertal dispatched by proxy (as Macbeth will have Banquo). He thus offers the jobless actor, the part he had been so desperate to play... that of a murderer... offstage. But as the intoxicated Sigurd fails to carry out his purpose – his gun jams and he knocks Bertal down on the head with the butt of the weapon which he drops before running away, persuaded that he has indeed killed the old man – Ludovic has no other choice than to pick up the gun and shoot Bertal himself.

19 One more major character type in noir films is the femme fatale. Absent in Barsacq where the only female character is Aurélia, a rather dull and disillusioned woman well past her prime (fig. 7) – although, like Lady Macbeth, she is the one to goad her husband into shooting the man under whose yoke they are being kept – the femme fatale motif is impersonated in Cukor’s A Double Life by the Venezia Café’s sexually provocative waitress whom Douglas Lanier describes as being just “one step away from prostitution and squalor” [23] (fig. 6). The towheaded waitress is seen slinkily hovering around Tony, slithering around him and brushing past him for physical contact. She erotically leans across the table to proffer a candle for him to light his cigarette. She tells him she is a masseuse which she pronounces with a voluptuous French intonation. Soon after she informs him at what time she finishes her shift, and invites him over to her place to talk about their troubles, she says. She finally scribbles her address on a slip of paper, which she puts down on the page of the Othello playbook Tony is reading. There and then it looks as if the open book has become some kind of palimpsest with a new text laid over it, printed over as it were, partly blotting out the original and adding new material, suggesting that she is unknowingly to become part of the Othello plot. That same night, Tony walks to her flat in a seamy part of town. It is almost reluctantly or absent-mindedly, his mind being full of the play, that he allows himself to be pulled into her bed. What happens between them next is occulted by a sudden fade-to-black which takes us to a private scene between Tony and Brita at lunch in her apartment. The white daylight coolness of the image shot against a window, and Brita and her environment’s cool sophistication convey the sense of Brita’s unresponsiveness to Tony, if not a certain frigidity. The transition technique seems to bring the two women together, but more importantly to iconize a displacement of the sexual act shifted from one woman to another. Furthermore, the cinematographic design vividly opposes the two relations, one taking place at night-time in a seedy neighbourhood and the other in daylight in a luxurious place. It is as if Tony led a double life, the film’s title, one public and socially respectable, the other secret and reprehensible. The black-out on the sexual act might be understood as a metaphor for Tony’s censoring, in the psychological sense of the character’s pushing back his acts from consciousness.

20 The other female character in Cukor is Brita (fig. 5), whom Douglas Lanier presents as Tony’s “sophisticated European co-star with whom he has an on-again, off-again marriage,” [24] and she too may appear like a femme fatale, although less conspicuously so and not of the seamy sort, but one all the same, who goes on both attracting and repulsing her ex-husband at the same time, and who will thus fuel his jealousy, his sense of male disintegration from a gender viewpoint, and bring about his downfall. Contrary to Desdemona, Brita bears some responsibility in Tony’s mental deterioration. Most essential to the film’s thematic development is the fact that the relation between Tony and Brita is inextricably woven into the very fibre of theatre. As Brita explains to Bill Friend, “[They] were engaged during Oscar Wilde, broke it off during O’Neill; [they] married during Kaufman and Hart, [25] and divorced during Chekhov” (12.49). At the beginning of the film, while playing Robert E. Sherwood’s comedy, A Gentleman’s Gentleman, they get on so well that they might consider marrying again. This past year, Brita confides to Tony, has been so wonderful that there have been times when she almost thought they might make it together again, if they tried. But Brita knows that if they “ever get mixed up in an Othello kind of thing, it will be the end” (14.19-14.31). Which it will. Thus, their relationship’s ups and downs are strictly conditioned by the seesaw succession of upbeat comedy and downbeat tragedy playing at the Empire Theatre in Broadway. Like many a noir protagonist, the characters are trapped, “hemmed in” [26] and their existences environmentally determined. No more than puppets, they are in fine imprisoned in their roles, and their whole lives, friends and connections are contingent on the overpowering world of the theatre.

Female characters in A Double Life and A Crimson Curtain

Fig. 5. “Sophisticated European co-star” Brita Fig. 6. Sexually provocative waitress

Fig. 7. Dejected Aurélia

The same and the other: resurgences of the femme fatale

Fig. 8. Brita as Desdemona Fig. 9. Desdemona-like waitress Pat Kroll

Fig. 10. Actress hired to play Pat

21 The journalist is another prominent character type in noir. [27] A dark and cynical gossip chaser, he is ready for just anything to secure a scoop. His is an unscrupulous yellow kind of journalism which exploits, distorts, exaggerates facts to better attract readers. Cukor himself satirizes a horde of hounding bloodthirsty reporters crowding into the cramped staircase leading to the victim’s lodging with their cumbersome cameras. Kept at bay outside the flat, they cannot wait to rush pell-mell into the room, as soon as the door opens (fig. 11), for some gruesome details and pictures of the body. Sometimes the columnist is the guy who unknowingly “stumbles on some key evidence,” making him instrumental to the investigation and some sort of “informal detective” (Willson, 90). This is what happens when, after the medical examiner’s account of this most unusual murder, Cukor’s Millard Mitchell’s tall, heavily-built, overbearing newshound Al Cooley grabs at the doctor’s lapel to draw him apart, and perceptively comes up with the catchword “kiss of death” to hook his readers. He wants to play it big. How he makes the connection between the murder and the Othello production is not quite clear, but he is next seen brushing past the secretary and bursting into the theatre press agent’s office. Slumping, uninvited, into a chair, he offers to hype the Othello show by moving it to the frontpage, to keep up the public’s interest as the play moves into its second year. His angle is to liken the crime to the manner of Desdemona’s death in the current Broadway production. Bill Friend hears the reporter out coolly at first but soon warms to the idea. After Cooley names his price the deal is clinched. He is therefore the one who unknowingly provides a clue for solving the murder.

Fig. 11. Al Cooley (left) and other journalists hungry for information

22 Poles apart from the newshounds is Bill Friend, not strictly speaking a newspaper man but the theatre press agent. He is what Ehrlich describes as the journalist-type “hero fighting and righting wrongs,” [28] not so much from any yearning for justice as from a desire for Brita. He is the one whose suspicions are aroused first, who shares his concerns with the police, who tries and frame Toni in the mousetrap piece asking for the police to watch from under cover; he is the one again who walks the police officer to the restaurant where Pat Kroll worked and gets information from the owner, and finally takes the man back to the theatre to nab the culprit. He becomes the noir type of the amateur private eye casting the official investigators into the shadows.

23 Barsacq does confide the murder case into the hands of the police, as it should be, but not without poking fun in so doing at the French law representatives, casting them into an inefficient Laurel-and-Hardy-type pair – the chief inspector in his late fifties, surly, gruff, put out at having to stay up late like a perfect French public agent, and ready to pin the murder on an old drunk so he can go home and hit the hay, but not without, mind you, having gulped down an omelette and a petit rouge at the bistro close by; the young officer, the former’s stooge, naïve, neglecting his duty to watch the play with a child-like excitement, and who in so doing accidentally helps solve the crime by drawing his chief’s attention to it. The Crimson Curtain also takes the mickey out of the traditionally inept French gendarme in his ridiculous mortarboard of a kepi. But what will bring irrefutable proof of the criminals’ guilt is the two journalists’ recording. We are back to the journalists-as-heroes motif, but not without Barsacq debunking the noir myth again.

24 The reporters, who work for the radio, are two callow youths, as keen as they are clumsy. Claiming to be interested not so much in Shakespeare as in Bertal himself, they turn the interview into a pseudo-investigation of the real-life characters, probing Bertal’s personal motives to pick this particular play. But Bertal suddenly feels faint and must have a lie down. He will finish off the recording on his own. It follows that the journalists’ pseudo investigation is put an end to when Bertal sends them packing. As they come back later that night to pick up their tape recorder, the chief inspector asks them, on a hunch, to play the device for him. Here are Bertal’s first words, then a pause, then Bertal picking up where he had stopped, then a long silence. And then, quite unexpectedly, Bertal’s words to Sigurd who says he has come to take his revenge, a scuffle, a knock and a grunt, footsteps quickly retreating. Another silence. The chief inspector bends eagerly over the reel as if to retrieve more. Oh, the luck of the devil! Bertal speaks up again, asking Aurélia if she has come to check that the job has been done. A new scuffle. A cry from Aurélia calling for Ludovic’s help. Hasty footsteps coming in. Three shots. The journalists, the traditional film noir righters of wrong, turn out to be ineffectual, their pseudo investigation aborting pitifully within seconds of the recording, which ironically will take care of itself.

25 The reporters and the police being relegated to their own ineptness, it is Bertal himself who will direct, not only the play within and his own murder, but also the investigation itself, first by having his lookalike (Léonard) cast as his own understudy, who will be seen as his own ghost risen from the dead to denounce his murderer, and then by exposing him through his recording – the tape recorder a variation of the ghost motif, here lending voice to the mute spectre of the banquet scene, and Bertal the great ordinator of all things. The tape recorder or other similar devices are definitely key elements film noir generally and in some of its most prominent landmarks like Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950) both directed by Billy Wilder (1944), or Touch of Evil by Orson Welles (1958), allowing the dead to speak from the grave. [29]

Fig. 12. The two journalists & police officers Fig. 13. The tell-tale tape recorder

around their piece of evidence

III. Setting

26 Film noir is often given an urban setting. Across the Atlantic where it was born, Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York and Chicago are staple noir locations. A Double Life follows suit by being set at the heart of New York, and more specifically at the Broadway Empire Theatre where the film opens and ends. Similarly, Barsacq’s piece takes place in the French capital at the Théâtre de l’Atelier on the butte Montmartre, a hill in northern Paris much frequented by artists in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Crimson Curtain likewise opens and closes on the very iconic playhouse. Although the basic layout is very much the same, the two filmmakers’ handling of space differs dramatically.

27 In A Double Life, the many pictures of blunt, rectilinear architecture, sharp skylines, steel beam structures, overhead railways, steep flights of stairs, made all the more overpowering by the frequent use of low-angle shots, imbue the cityscape with a coldness, a harshness and a crushing weight which are those of merciless modern society.

28 If most of A Double Life revolves around the theatre, understandably necessary for the Shakespearean play’s rehearsals and performances, Cukor polarizes two locations, the well-off and elegant Broadway neighbourhood related to the sophisticated Brita, and the squalid, dreary, low-class suburb associated with the waitress, Pat Kroll. Douglas Lanier rightfully claims that Tony is torn between these two socially marked milieus. [30] Sprung from the working class (his father who had tried for a career as an actor ended up a doorman), Tony strenuously worked his way up, explaining how he had to teach himself how to talk and move and think, how he had to tear himself to pieces and put himself together again (07.05).

29 The first time Tony goes to the waitress’s place after his dinner at the Venezia Café, it is just before the company has started working on the Othello play. Still in the mood of the current performing of the farce, A Gentleman’s Gentleman, he strolls leisurely, cool-headed and smiling, through the dark streets of night-life New York past a railway to Pat Kroll’s apartment block. Two shots, articulated by a dissolve, take him quite straightforwardly to the place. But when he returns to her flat after Othello nightly performances have come into their second year, and he has had a serious quarrel with Brita prompted by his obsessive jealousy, he is all churned up inside. The passage is very artfully crafted. In a series of shots and dissolves that take two full minutes (56.06-58.01), the montage shows Tony drunkenly and haltingly prowling through the dark seedy streets and side-alleys, looking back and around, his eyes wild, in a confused state of mind, only half-aware that his steps are taking him to Pat’s. As he distractedly wanders, the almost motionless camera provides long shots of the protagonist walking either towards or away from it, diminishing or growing in size as he does so. Alternately, the device pans sideways, left or right, to follow Tony. Back and forth, left and right. By its destructuring and disorientating effect the camera turns the city into a dark labyrinth, [31] fully expressive of Tony’s utter mental confusion. The maze-like cityscape is a mindscape.

30 On the other hand, The Crimson Curtain with very few outdoor scenes, is almost a huis-clos set in a cramped area formed by the theatre itself and the café around the corner where the actors are in the habit of having a drink or meal. [32] Despite resorting to the same urban setting, symbolically the hub of human interactions and conflicts, the two films diverge radically. Cukor highlights his character’s physical vagrancies as an expression of his mental disorder while Barsacq lays the stress on the stifling theatrical world of his protagonists in which they are trapped.

31 Apart from the general urban setting of many film noirs, critics have identified more specific industrial settings, like refineries, factories, power plants or trainyards. [33] Like the roaring train in Tennessee William’s A Streetcar Named Desire, the elevated railway is part of Pat Kroll’s working-class environment. The two times Tony walks to her place, a train loudly tears past. Once inside her flat, more trains go by, and the shattering sound is such that it momentarily covers their conversation. The wild rattling sound will eventually jar Toni’s mind to such a degree as to confuse “reality” and the world of the stage, resulting in the death of Brita/Desdemona-like Pat Kroll. Nothing of the sort is found in The Crimson Curtain due to its more theatrical nature: Barsacq is a theatre man, The Crimson Curtain his only fling at cinema, shot on location in his own playhouse, following the time and place rules of classical drama.

32 Another type of setting fit for noir protagonists are bars or cafés, often grimy and smoke-filled. They play a major role in both Cukor and Barsacq, although they are just mildly popular, and not of the rough kind: it is the Venezia restaurant where Toni meets Pat Kroll, the other bar where Bill Friend tries to trap him; the small bistro around the corner frequented by actors, where Ludovic and Aurélia have a quick bite before the performance and where they are joined by the actor Sigurd; and where again the chief inspector dines while slyly grilling the owner.

Fig. 14. Bleak night cityscape Fig. 15. Rain-washed street,

extreme high-angle shot

Fig. 16. Rain-washed street at night Fig. 17. Theâtre de l’Atelier at night

33 Metaphorical of the characters’ dark and tumultuous minds, classic noir often involves night scenes and rainy or stormy weather. Connected with the theatre, both A Double Life and The Crimson Curtain understandably take place mostly at night. Barsacq’s film takes place thoroughly at night, starting with a late afternoon short rehearsal and ending at the end of the night performance when the public disperses. As to Cukor, he either sets his scenes indoors, where artificial lights make it difficult to distinguish between day and night, or decidedly out of doors after the performances. Rain-washed asphalt typically glistens under artificial street lights in both films. And the storm element, complete with lightning and thunder, required by the playwright’s stage directions in Macbeth, and added by Cukor and his team to the last scene of Othello, is there to reflect the characters’ raging passions.

34 Of course, film noir has other characteristics such as typical visual codes: black and white, day-for-night shooting, stark contrasts between shade and light, dramatic shadow patterning, sidelighting, crafty compositions with bed-railings or banisters behind which the characters are trapped, skewed low- or high-angle shots. The same disorientating effects are reached by playing with various reflecting surfaces like mirrors, shop windows or shooting through frost-glass doors, etc. Distortion of sounds is also at work, be it the jarring sound of pendeloques as Tony hits them, first involuntarily and then purposefully, the thundering sound of trains tearing past, the smashing of glass, etc. Disrupting or confusing structural devices are also noir specificities like flashbacks, dissolves or voice-over. But there is no room for these considerations here.

35 It may be concluded that Cukor fits perfectly well within the noir tradition, with a focus on the femme fatale and the psychologically unstable male character sort. Barsacq’s later piece shifts to harsher motifs, as noir did over time: the hard-boiled man, alcohol and drugs, cynicism, which might have made The Crimson Curtain darker, more squalid, were it not for the humour and playful deriding of noir features pervading the film: the inept police and journalists, an investigation that depends on chance findings, the doppelgänger motif, the depressive femme fatale, the laughable homicidal washed-up actor, playlets that will only mislead the police to pin the crime on the wrong man, by which the theatre man gently pokes fun at his transatlantic model and the typically American noir genre of the time.

Summaries

Summary of Cukor’s A Double Life (1947): Anthony John (Ronald Colman), a seasoned middle-aged actor, is pressured into playing the title role in a stage adaptation of Othello while his ex-wife, Brita Kaurin (Signe Hasso) is to share the stage with him as Desdemona. The couple had been “engaged during Oscar Wilde, broke it off during O’Neill; [...] married during Kaufman and Hart, and divorced during Tchekhov” (12.48). Ever since they have been entertaining a flirtatious relationship with Anthony – nicknamed “Tony” throughout the film – pressing Brita to marry him again. Tony’s compliance to play the tragic lead, Brita fears, will be the end of their relation. And Tony himself confides: “I have a feeling it isn’t the sort of thing I ought to do.”

The first few hundred feet of film then set the tone by creating an atmosphere which is thick with foreboding. As Tony casually flips through the pages of the play and the book falls open at the beginning of Act III, Scene 3, he reads to himself in voice-over above a haunting music: “O, beware, my lord, of jealousy, / Which is the green-eyed monster” (II.3.169-70).

Brita obstinately refuses to marry him again. And soon he becomes neurotically engrossed with the press agent, Bill Friend (Edmond O’Brien), whom he suspects of trying to seduce Brita, even though she seems unaware of, or indifferent to, his attentions. Day after day, the rehearsals take their toll on Tony’s mind. He reflects: the “part begins to seep into your life. [...] And the battle begins: imagination against reality – keep each in its place – that’s the job, if you can do it.”

Then the performances begin. Night after night. Soon the show reaches its 200th night. Shortly after a poster announces the 300th performance. Tony’s mind is by then thoroughly pervaded by the Moor’s cankerous jealousy. As Tony goes through Act V, Scene 2, the battle he has been fighting to keep “fiction” and “reality” apart is lost. He would have strangled Desdemona/Brita had it not been for the backstage staff pressing themselves on the brink of the stage and calling to him as “Mr John”, and Brita begging him, “Tony”, not to squeeze her throat so hard.

The production is now in its second year. A scene breaks out between Tony and Brita as she one more time turns down his proposal to marry again, which leads to a new spurt of jealousy. As he feels uncontrollable fierceness rising in him, he forces himself to leave her place. He roams through the streets until his steps take him to where lives a casual mistress of his, Pat. She reluctantly lets him in.

After a short trivial exchange, Tony wants to know how many “types” she has had, if she has had any press agent, any named Bill. The deafening sound of a train thundering past jars him out of his frayed composure. When the Desdemona-like Pat (Shelley Winters), with her long floating blond hair, in her white nightdress, sits on her white-canopied-bed and invitingly calls to him to “put out the light”, her cue-like words act like a push-button, prompting Tony’s automated lines after countless nightly repeats. He kills Pat in a “death kiss”. The forensic examination concludes: “neck, throat unbruised, trachea, larynx, windpipe intact [...] small pressure markings above and below lips” (01.06.19).

A journalist becomes aware of an odd likeness in the way Pat Kroll was murdered and the current Broadway production. The following day the New York Star publishes an article on “Othello murder”. Suspecting Tony to have been involved in the case, Bill goes down to the police. But he is told the murderer, an old sot living across the hall from her, has been nabbed. The police confide that they had had suspicions about Tony and that they looked carefully into it but that he had an alibi.

As Bill goes to Brita to tell her he is taking a few weeks off, he understands that Tony didn’t spend the whole night at her place and that he is not actually cleared. He decides to trick him by inviting him over to a bar where he has a wigged actress resembling Pat Kroll and wearing the same earrings work as waitress under the scrutiny of a police officer. Unhinged by the likeness and jarred by the shattering of glasses, Tony rushes out of the place telling Bill he will be seeing him later at the theatre.

This is not proof enough for the police. Back at the theatre, Tony collapses in Brita’s arms, insisting that he is in no condition to play that night (as Ludovic will in The Crimson Curtain) but she pushes him on (as Aurélia will).

Meanwhile Bill and the police officer go to the Venezia, the restaurant where Pat Kroll worked, and question the owner who reports to them that Tony dined there and made a date with the waitress.

The three men walk to the theatre and take a place backstage behind the set. The performance is drawing to its close. As Tony/Othello’s eyes rest on the Venezia owner and police officer, his mind breaks to pieces. He doesn’t speak on cue and needs some prompting from either a fellow actor who has to repeat his words to him or from backstage, or he speaks out of turn and changes his play, unraveling the warp and weft threads of the canvas, the interweaving of his acting with that of the other actors. But increasingly his own thread becomes frayed to the point of breaking as he staggers – rather than walks – from one actor to the next, repeats some of his words to give himself time to retrieve the forgotten lines in a seesaw movement, or utters his lines haltingly before he stabs himself silent with a real dagger.

Summary of Barsacq’s Crimson Curtain (1952): Ludovic Harn (Pierre Brasseur) and Aurélia Nobli (Monelle Valentin) have been lovers for years. They are both actors in the theatre company directed by Lucien Bertal (Michel Simon), Aurélia’s common-law husband who has been aware of their relationship all along. A drug-addict, Bertal has sadistically been keeping the lovers under his thumb by supplying Ludovic his daily fix.

He has lately been working at putting on a new stage show, Macbeth, which he views as “one of the harshest” of Shakespeare’s creations, in which Ludovic and Aurélia are to play the title roles. One can imagine that, as they go through the many rehearsals that must have preceded the opening of the film, endorsing the roles of murderers and dipping their hands into Duncan’s blood day after day, the dividing line between the Shakespearean world and that of the actual Parisian playhouse of the early fifties becomes increasingly blurred. Ludovic and his mistress become obsessed with getting rid of the nasty old man and end up carrying out the deed.

An old drunk, to whom Bertal refused a part in the play, boasts he will bump the man up. He is arrested while carrying a gun in the first moments of the investigation. The plot could have been just that but for the scriptwriters’ shrewd minds (André Barsacq and Jean Anouilh). Bertal’s murder being carried out within minutes of the curtain raising, the slaying of Duncan becomes a particularly nerve-wracking experience for Ludovic/Macbeth who is made to repeat the earlier off-stage assassination. Haunted by their evil deed, both actor’s and character’s minds slowly disintegrate as the performance proceeds.

The scriptwriters’ master stroke resides in having Bertal’s understudy as Banquo played by the selfsame Michel Simon, prompting an intricate doppelgänger game. Once Banquo disposed of, the Banquet scene (III.4) has Ludovic/Macbeth face each his victim’s telltale ghost: Macbeth falls apart trying to dismiss Banquo’s spectre back into his charnel-house while Ludovic breaks down in front of Bertal’s phantom. In a fit of despair, he throws himself upon him, grabs him at the throat, and tries to get rid of him for good, at the same time giving himself away.

Notes

1. A Double Life won two Oscars and one Golden Globe, and received two Oscar nominations, and one Grand International Award nomination at the 1948 Cannes Festival. Ronald Colman was awarded an Oscar for the best actor in a leading role.

2. Rothwell, Kenneth S. A History of Shakespeare on Screen. A Century of Film and Television. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. 219. Cary M. Mazer categorizes such metatheatrical productions as “rehearsals-of-a-Shakespeare-production-within-a-film.” Mazer, Cary M. “Sense/Memory/Sense-Memory: Reading Narratives of Shakespearian Rehearsals”. Shakespeare Survey. Vol. 62 (2009): 330. Cited by Kinga Földváry. “Mirroring Othello in Genre Films: A Double Life and Stage Beauty”. Ed. Sarah Hatchuel & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. Shakespeare on Screen: Othello. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 178.

3. Silver, Alain & Elizabeth Ward (Eds). Film noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style. Third edition. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press, 1992 [1980]. 94-95.

4. On A Double Life as noir: Willson, Robert F., Jr. “A Double Life: Othello as Film noir Thriller”. Shakespeare on Film Newsletter. Vol. 11, n°1 (1986) : 3, 10 (2 pages); Lanier, Douglas M. Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 67-68; Lanier, Douglas M. “Murdering Othello.” Ed. Deborah Cartmell. A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation. Chichester, UK / Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. 198-215; Földváry, Kinga. “Mirroring Othello in Genre Films: A Double Life and Stage Beauty”. Ed. Sarah Hatchuel & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. Shakespeare on Screen: Othello. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 177-94.

5. Arthur, Paul. “Murder’s Tongue: Identity, Death, and the City in Film Noir.” Ed. J. David Slocum. Violence and American Cinema. London & New York: Routledge, 2001, p. 160. See also the well-documented article on “Film noir” from Wikipedia which offers a helpfully condensed overview of characteristically noir themes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_noir). Consulted 20 November 2024.

6. This “kiss of death”, as a journalist’s catchphrase in the film has it (01.06.55), is Tony’s innovation from the strictly Shakespearean strangling or stifling with a pillow. Robert F. Wilson Jr. comments that although this is an anatomically impossible death, the “kiss that kills” conceit epitomizes the deeply ingrained oxymoronic love/death motif of the play. This “kiss of death” recalls the title of another film noir by well-known director Henry Hathaway released the same year. But as it was first screened by 20th-Century-Fox on 27th August 1947 only four months before Cukor’s A Double Life (25th December 1947), it is difficult to establish that the death kiss motif was inspired by Hathaway’s film. Kinga Földváry may be mistaken when she claims that “half a year after A Double Life, another film noir was released with the title Kiss of Death, most probably feeding on the marketing opportunities offered by the success of A Double Life” (p. 185) since Hathaway’s footage was released before A Double Life, not after.

7. I have increased the light of all the screenshots by 10% to make the details more visible.

8. See also The Saint’s Double Trouble (dir. Jack Hively, 1940), The Man with my Face (dir. Edward Montagne, 1951). A variation of the look-alike character, twins are at the core of Among the Living (dir. Stuart Heisler, 1941), The Dark Mirror (dir. Robert Siodmak, 1946), The Guilty (dir. John Reinhardt, 1947), I Cover the Underworld (dir. R. G. Springsteen, 1955), and House of Numbers (dir. Russell Rouse, 1957). Both lists are not exhaustive. Paul Arthur estimates that there are a dozen films noirs revolving around the narrative trope of the slaying of a doppelgänger (p. 161).

9. See Deangelis, Michael. “Doubling in the Cinema of George Cukor: The Royal Family of Broadway, A Bill of Divorcement, A Double Life, and Bhowani Junction.” Ed. Murray Pomerance & R. Barton Palmer. George Cukor: Hollywood Master. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015, pp. 92-106.

10. For more detail, see Dorval, Patricia. “Specularity in André Barsacq’s Crimson Curtain (1952).” Ed. Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 6. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2024. Online: https://shakscreen.org/analysis/dorval_2024a/.

11. In the Shakespearean play, Macbeth does not witness Banquo’s murder perpetrated by his henchmen.

12. For more details on other less significant metadramatic pieces, see my “Macbeth et Le Rideau rouge d’André Barsacq (1952): des figures d’enchâssement à la mise en abyme.” Ed. Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 3. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2014. Online: http://www.shakscreen.org/analysis/analysis_rideau_rouge_figures_enchassement/.

13. First briefly drawn by Robert F. Wilson Jr (1986), p. 10, the comparison is further developed by Douglas Lanier (2012), pp. 198-99.

15. Wikipedia/Laura Cremonini.

16. Naremore, James. Introduction to Borde, Raymond & Étienne Chaumeton. A Panorama of American Film noir (1941-1953). Trans. Paul Hammond. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2002, p. xii. Originally published as Borde, Raymond & Étienne Chaumeton. Panorama du film noir américain 1941–1953. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1955.

17. Ballinger, Alexander & Danny Graydon. The Rough Guide to Film Noir. London & New York: Rough Guides Ldt, 2007, p. 33.

18. Hirsch, Foster. The Dark Side of the Screen: Film noir. New York: Da Capo, 1981, p. 194.

20. “Je ne sais pas ce qui les collait ensemble ces trois-là.”

22. See for instance Hirsch, p. 12 (“in general noir heats up, gets crazier, toward the latter part of the 1940s”) & p. 202 (“The contrasting late noir tendency is exaggeration”), and Paul Schrader. “Notes on Film Noir” (1972). Film Noir Compendium. Ed. Alain Silver & James Ursini. Milwaukee: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2016, pp. 89, 92-93.

25. American playwrights George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart wrote a number of comedies together, notably Once in a Lifetime (1930), You Can’t Take It with You (1936) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939).

27. Ehrlich, Matthew C. Journalism in the Movies. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004, p. 79. The whole of Chapter 5 focuses on journalism in film noir, pp. 79-104.

29. Playing on noir themes and set in 1947, the television series Ratched (dir. Ryan Murphy & Evan Romansky, 2020) relies on the same device. All Night Long, directed by Basil Dearden (1962), to which Douglas Lanier drew my attention, works differently. Following the Othello plot, this noir-esque British film substitutes the tape recorder for the original eavesdropping scene: Johnny/Iago turns on a tape recorder (meant for the outstanding performances of a jazz band) in order to capture Cass/Cassio’s conversation first with his girlfriend, Benny, and then with Delia/Desdemona. He then tampers with the reel, cutting the pieces that don’t serve his purpose, and reassembling the material into an entirely new montage, which he has Rex/Othello listen to as proof of his wife’s unfaithfulness.

31. See for instance Nicholas Christopher, who has a full chapter on the labyrinth (Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City. New York: The Free Press, 1997, pp. 1-32).

32. Hirsch opposes the studio-made films providing an appropriate backdrop for stories of entrapment (in The Crimson Curtain, the chief inspector wonders repeatedly why the couple did not leave and what glued them together) to real cities thrillers shot on location. The first are “claustrophobic psychological studies, stories of obsessions and confinement in which the world begins small and then progressively closes in on the fated protagonist” (p. 15), or in other words “closed-form stories of festering neurosis” (p. 17). But after the war, “the thriller took to the streets of real cities” (p. 15). Taking the example of Night in the City (dir. Jules Dassin, 1950), Hirsch describes the setting as “a real London, oozing with slime and enshrouded with fog”, which “becomes a maze of crooked alleyways, narrow cobbled streets and waterfront dens: a place of pestilential enclosure” (p. 17). Whether the film is set in a confined space like the theatre (a variant of the film studio) in Barsacq’s Crimson Curtain or in a wider maze-like environment as in Cukor’s A Double Life, the result is the same sense of entrapment and inescapability. One hero suffocates, the other blunders about, but neither will find a salvatory exit.

33. Wikipedia/Laura Cremonini.

Bibliography

- Arthur, Paul. “Murder’s Tongue: Identity, Death, and the City in Film Noir.” Ed. J. David Slocum. Violence and American Cinema. London & New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 153-75.

- Ballinger, Alexander & Danny Graydon. The Rough Guide to Film Noir. London & New York: Rough Guides Ldt, 2007.

- Christopher, Nicholas. Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

- Cremonini, Laura. Ten Masterpieces of Noir Cinema. Self-Publish, 2020. Online: https://www.google.fr/books/edition/Ten_Masterpieces_of_Noir_Cinema/ilXsDwAAQBAJ?hl=fr&gbpv=1&dq=industrial+settings,+trainyards+in+film+noir&pg=PT78&printsec=frontcover. Available on Wikipedia at “Film noir” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_noir).

- Deangelis, Michael. “Doubling in the Cinema of George Cukor: The Royal Family of Broadway, A Bill of Divorcement, A Double Life, and Bhowani Junction.” Ed. Murray Pomerance & R. Barton Palmer. George Cukor: Hollywood Master. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015. 92-106.

- Dorval, Patricia. “Macbeth et Le Rideau rouge d’André Barsacq (1952): des figures d’enchâssement à la mise en abyme.” In Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 3. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2014. Online: http://www.shakscreen.org/analysis/analysis_rideau_rouge_figures_enchassement/.

- ⸺ “Specularity in André Barsacq’s Crimson Curtain (1952).” Ed. Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 6. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2024. Online: https://shakscreen.org/analysis/dorval_2024a/.

- Ehrlich, Matthew C. Journalism in the Movies. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

- Földváry, Kinga. “Mirroring Othello in Genre Films: A Double Life and Stage Beauty”. Ed. Sarah Hatchuel & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin. Shakespeare on Screen: Othello. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 177-94.

- Hirsch, Foster. The Dark Side of the Screen: Film noir. New York: Da Capo, 1981.

- Lanier, Douglas M. Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ⸺ “Murdering Othello.” Ed. Deborah Cartmell. A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation. Chichester, UK / Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. 198-215.

- Mazer, Cary M. “Sense/Memory/Sense-Memory: Reading Narratives of Shakespearian Rehearsals”. Shakespeare Survey. Vol. 62 (2009). 328-48.

- Naremore, James. Introduction to Borde, Raymond & Étienne Chaumeton. A Panorama of American Film noir (1941-1953). Trans. Paul Hammond. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2002. Xii. Orgininally published as Borde, Raymond & Étienne Chaumeton. Panorama du film noir américain 1941–1953. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1955.

- Rothwell, Kenneth S. A History of Shakespeare on Screen. A Century of Film and Television. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Schrader, Paul. “Notes on Film Noir” (1972). In Alain Silver & James Ursini (eds). Film Noir Compendium. Milwaukee: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2016. 89-100.

- Silver, Alain & Elizabeth Ward (Eds). Film noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style. Third edition. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press, 1992 [1980].

- Willson, Robert F., Jr. “A Double Life: Othello as Film noir Thriller”. Shakespeare on Film Newsletter. Vol. 11, n°1 (1986) : 3, 10 (2 pages).

How to Cite

DORVAL, Patricia. "The Crimson Curtain (1952) in the Mirror of A Double Life (1947): The Film noir Tradition: Plot, Characters, Setting." In Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 6. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, 2024. Online: https://shakscreen.org/analysis/dorval_2024b/.

Contributed by Patricia DORVAL

<< back to top >>