When Shakespeare Met Romantic Comedies…

Frédéric Delord

Introduction: Quand notre cœur fait boum – or my heart goes boom

1 This essay will focus primarily on the allusion to Romeo and Juliet in Claude Pinoteau’s La Boum (1980, English title(s): The Party or Ready for Love). I have contributed three times to “shakscreen” but each time, my attention has lingered on highbrow and rather intellectual arthouse Francophone films (directed by European directors André Téchiné, Michael Haneke and Manoel de Oliveira). I had come to believe that erudite allusions were particularly pregnant when they occurred in such films. However, the Shakespearean allusion in La Boum was one of the first entries created on our database. I cannot remember now whether Mariangela Tempera had already found it when she presented her project to French academics (or whether it was one of the first instances that popped into my mind) but in any case, the entry has been on our site since the very beginning of its existence. It is a film, I must add, that I have seen countless times. I was born in 1979 and I think a lot of 40-something-year-olds will agree that the film has played a major part in the pop culture of their/our generation. I remember that when we presented the database during a conference dedicated to Macbeth on Screen (2013), a colleague’s eye was immediately drawn to this particular entry: “La Boum – what’s the Shakespearean reference in La Boum?” he asked. I want to examine the potentiality of such an intertext in a nonetheless extremely popular and entertaining rom-com teen movie, at a time and place when such “genres” were in reality not referred to as such: the 80s in France.

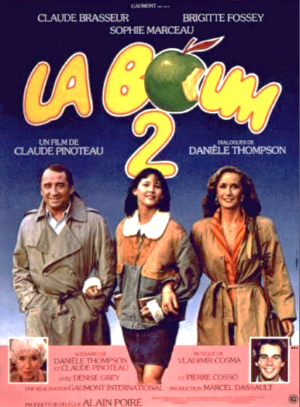

2 The film is also very popular in Italy, which explains why Mariangela Tempera might have known it already: it is entitled Il Tempo Delle Mele, which translates “the time of apples”, a rather puzzling title. One politically correct interpretation could be that the film, being a coming-of-age story, deals with the notions of maturity – apples falling when ripe. Another, rather awkward and inappropriate interpretation of the title, metaphorically associates apples with the development of young breasts during teenage years. The Italian title has had such influence that the sequel to the film, aptly named La Boum 2 (1982) (and although it still makes no mention of apples) incorporates an apple in its logo.

3 The film is so popular in Italy that the third collaboration between Claude Pinoteau (director), Danièle Thompson (screenwriter) and Sophie Marceau (lead actress), which recounts the love life of a young woman who prepares for the agrégation (L’Étudiante, known in English as The Student, 1988) was christened Il Tempo Delle Mele 3 there. Pinoteau and Thompson, though, have always been adamant about the fact that L’Étudiante was never meant to be “La Boum 3” as the film was initially written for Isabelle Adjani – who is traditionally seen as more bookish and brainy than Marceau. The main character is no longer called Victoire, as in La Boum, but Valentine. In 2008, director Lisa Azuelos paid homage to La Boum with her film LOL, a teen movie that she wrote and directed, in which Marceau interprets Anne, the 40-year- old mother of a teenage daughter. The loop was finally looped. The Italians, expectedly, re-entitled the film LOL – Il Tempo Dell’amore.

4 Not only has La Boum had a European career (it is also quite famous in Germany, under the title Die Fete [The Party] – we will mention a particular scene from the German dubbed version later), but it has also become a worldwide success, particularly in Asia. For the readers who have never seen the film, or barely remember it, I recommend watching the following “Blow-up” videos, broadcast on Arte:

5 But before tackling the issue of the allusion to Romeo and Juliet in La Boum, we need to set context – and, more particularly, present a broader reminder of the interactions Shakespeare and romantic comedies have entertained over the years. Why do we need this detour? Because if we manage to determine that there is a Shakespearean quality to romantic comedies, and that there is something structurally Shakespearean to that genre, we will be able to make the most of the allusion in the film. In other words, our theory is that the Shakespeareanity of La Boum is perhaps not only limited to its obvious Romeo and Juliet-ness.

I. Context: a brief history of the rom-com in France and the U.S.

Film scholars explain that romantic comedy is a process of orientation, conventions, and expectations (Neale and Krutnik 1990: 136-49). The film industry orients audiences […] by casting stars identified with the genre like Meg Ryan[.] Filmmakers adapt conventions from successful films in the genre, while adding new elements to keep the movie fresh. […] The plot of most romantic comedies could be presented with the earnestness of melodrama, but the humorous tone transforms the experience. The movie assumes a self-deprecating stance which signals to the audience to relax and have fun, for nothing serious will disturb their pleasure. [1]

6 “Shakespeare crafted the genre of Romantic Comedy.” [2] “I read it on the internet so it must be true,” as the popular saying goes. Of course, the reality is slightly different. Indeed many elements which helped define the codes of 20th-century romantic comedies on screen were already structural to Shakespeare’s romantic comedies: love at first sight, star-crossed lovers, mistaken identities and ensuing misunderstandings, deus-ex-machina resolutions, happy endings and inevitable wedding ceremonies. Still, Shakespeare certainly was not the first playwright or author to use these tropes. Shakespeare’s romantic comedies feed off Aristophanes, Ovidian myths, medieval European courtly love, Chaucer, pastoral romances or Italian commedia dell’arte amongst other sources. Nevertheless, let us note that the blogger quoted above does not declare that Shakespeare “invented” the genre, she states that he “crafted” it – and it is fair enough to assume that he helped shape that particular narrative, assembling sources, determining plot devices and dramatic structure, and, above all, transmitting his art to posterity by popularizing a particular narrative pattern.

a. Shakespeare and the screwball comedy

7 One consistent feature within critical apparatus concerning Much Ado About Nothing is summed up by Sylvère Monod as such: “la comédie jouée par Béatrice et Bénédict […] ne semble pas avoir de source autre que la libre invention de Shakespeare.” [3] According to public academic opinion, the “Beatrice and Benedick” storyline has no official known source – or, at least, there has been no clear academic consensus about it – [4] which corroborates the idea that Shakespeare fathered modern romantic comedy. What is also particularly characteristic of the way Benedick and Beatrice fall in love is the importance of their respective egos: they fall in love with each other only when they are made to believe, through staged eavesdropping, that they are the object of one another’s affection – a trick René Girard calls “Love by hearsay.” [5] This device has not been systematically reprised in rom-coms though, as it clearly “de-romanticizes” the ideal of earnest and true love: the lovers fall in love with the image of themselves that is reflected back to them rather than with the supposed loved one. Yet in one of France’s most famous romantic comedies and box office successes, Amélie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001), a character reveals the “recipe” of love by hearsay:

8 I find this apparently trivial detail crucial. Indeed, one of the subgenres of romantic comedies and, in my very own biased opinion, the best instances of romantic comedy in films, was fashioned after the seminal archetype of older bantering lovers embodied by Benedick and Beatrice: this subgenre is called “screwball comedy” or comedy of remarriage. [6] Indeed the film that has been traced down to be the first romantic comedy ever produced (or considered the template for them all) is a screwball comedy titled It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934). [7] Two strangers (Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert) who rejoice in throwing zingers at one another see their initial dislike turn into true feelings of love. This genre distances itself from purely romantic comedies in that screwball comedies involve more mature main characters, and witty one-liners, which often make for better dialogue. Other examples of the genre include classics such as The Shop Around the Corner (Ernst Lubitsch, 1940) and The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940) with Katherine Hepburn (who incidentally starred in the longest running Broadway production of As You Like It).

9 The romantic comedy and its avatars and subgenres emerged in the 30s, thrived in the 50s and 60s (notably through Doris Day’s and Marilyn Monroe’s personas) and slowly started falling into desuetude by the early 70s – a much more political era in American cinema. Romantic comedies then morphed into romantic dramas (see the overly lacrimal Love Story, Arthur Hiller, 1970) sometimes imbued with political undertones (see Barbra Streisand’s character, a political activist, in the still very sentimental The Way We Were, Sydney Pollack, 1973). Romantic/screwball comedies gained newfound respectability when Nora Ephron and Bob Reiner reinvented the genre with When Harry Met Sally (1989), triggering a rom-com Renaissance. [8] Harry and Sally are 30-something rather than 20-something characters. They start their relationship by hating each other; they wittingly and wordily exchange with one another; and run into each other (that one time they finally end up getting along) in Shakespeare & Co Booksellers, New York – so many clues which could corroborate a reading of the film as a loose rewriting of the Benedick/Beatrice narrative. The following screenshot is an interesting metaphor of the way Shakespeare hovers over romantic comedies. Although not explicitly quoted, the playwright can still be seen in the background, almost winking at the spectator.

10 Meg Ryan subsequently became the queen of the rom-com (Sleepless in Seattle, You’ve got Mail, Nora Ephron, 1992 and 1998) only to be competed with (and finally deposed by) Julia Roberts (Pretty Woman, Gary Marshall, 1990 – My Best Friend’s Wedding, P. J. Hogan, 1997, amongst others) and Sandra Bullock (While You Were Sleeping, Jon Turteltaub, 1995 – Forces of Nature, Bronwen Hughes, 1999 – Two Weeks Notice, Marc Lawrence, 2002 or The Proposal, Anne Fletcher, 2009). Similarly, Sophie Marceau – although she starred in many of her ex-partner’s, Andrzej Żuławski, anti-mainstream art-house “difficult” productions such as L’Amour Braque (1985), Mes nuits sont plus belles que vos jours (1989), La Note bleue (1991), La Fidélité, (2000) – simultaneously became very much attached to romantic comedies throughout her career with La Boum (Claude Pinoteau, 1980), La Boum 2 (Claude Pinoteau, 1982), L’Étudiante (Claude Pinoteau, 1988), Fanfan (Alexandre Jardin, 1993), LOL (Lisa Azuelos, 2008), L’Âge de raison (Yann Samuell, 2010), Un bonheur n’arrive jamais seul (James Huth, 2012), Une rencontre (Lisa Azuelos, 2014); and sometimes to period-piece romantic comedies à la Shakespeare in Love like La Fille de d’Artagnan (Bertrand Tavernier, 1994) or Marquise (Véra Belmont, 1997) – she even played Hippolyta in Michael Hoffman’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1999)!

b. La Boum within the genre of French romantic comedies

11 My theory, then, is that La Boum is both the first French rom-com of the modern era and the first French teen comedy, and that it should be considered just as pivotal to the genre in French pop culture as When Harry Met Sally has been in America. The parallel between Nora Ephron (who wrote but did not direct When Harry Met Sally) and Danièle Thompson (who wrote but did not direct La Boum) is particularly striking. Nora Ephron was born in 1941 to Jewish parents (screenwriters Phoebe and Henry Ephron) while Danièle Thompson (née Tannenbaum) was born in 1942 in a family of Jewish descent (her father was screenwriter/director Gérard Oury). Ephron and Thompson were both screenwriters who later became directors in a profession dominated by men. Thompson prefaced the French edition of Ephron’s novel Heartburn and adapted her play Love, Loss, and What I Wore (2008) for the French stage (L’Amour, la mort et les fringues, 2011). [9]

12 La Boum helped define the romantic comedy genre in France because it is a film centered on relationships set in an urban and contemporary environment, when romanticism was then so often linked to historical period pieces or adventure comedies. French comedies heretofore had only been incidentally “romantic” (that is, featuring a female love interest for the male lead) in films mainly belonging to another genre – an aspect which interestingly poses the question of both genre and gender (female representation in films). Romantic comedies, although they often offer a formulaic script based on the boy-meet-girl trope that certainly tightens the shackles of sexist discourse, have also constituted an opportunity for actresses to be the lead in films often written or/and directed by women. [10]

13 Romanticism was a much less prominent concern in French films in the 30s and the 40s than it was in the U.S. Danielle Darrieux may be the actress who best epitomized good old-fashioned romanticism on screen with historical romantic dramas such as Mayerling (1936) or Katia (1938) with occasional light-hearted comedies (Premier rendez-vous). Catherine Deneuve then took over the role of the ingénue (La Vie de château, Jean-Paul Rappeneau, 1965) along with her sister Françoise Dorléac (L’Homme de Rio, Philippe de Broca, 1964) in adventure comedies, often revolving around stolen pieces of art, mysteries, investigations and exotic landscapes. Deneuve also interpreted the impetuous bitchy girlfriend [11] in formulaic fish-out-of-water stories such as Le Sauvage (Jean-Paul Rappeneau, 1975) and later, the very similar (almost copycat) L’Africain (De Broca, 1983). French romantic comedy was thus a subgenre which could not stand on its own, always associated with another more popular respectable genre which gave substantial roles to men, when women were reduced to portraying mere attractive sidekicks and sexy stooges (see “buddy” film Un éléphant, ça trompe énormément, Yves Robert, 1976) – with the exception of Jacques Demy’s musical comedy Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1966). Three comedies “of manners” (comédies de mœurs), La Gifle (Claude Pinoteau, 1974), Cousin, Cousine (Jean-Charles Tacchella, 1975, written by Danièle Thompson) and Diabolo menthe (Diane Kurys, 1977) also paved the way for La Boum.

14 These chronological landmarks are vital to understanding La Boum, for the film (which would now fall into the “rom-com” and “teen movie” categories: slapstick fun, cuckolded husbands and wives embroiled in love triangles with a pair of 13-year-old lovers at the centre of it all) was merely labelled a “comedy” in the 80s, at a time when the very concept of romantic comedy (a genre belonging to the English-speaking culture) was unknown to the French.

II. A possible Shakespearean reading of La Boum?

15 I want to make it clear that I am not interested in Pinoteau’s and Thompson’s conscious intentions concerning the Shakespearean intertext in their film. I am more interested in what the film itself has to say.

We know that a text does not consist of a line of words, releasing a single “theological” meaning (the “message” of the Author-God), but is a space of many dimensions, in which are wedded and contested various kinds of writing, no one of which is original: the text is a tissue of citations, resulting from the thousand sources of culture. [12]

16 An aesthetic object such as a film which has been written, directed, performed and edited can eventually be read, outside of the “author”’s reach, and its reading can reveal elements that escaped the author’s knowledge. Sometimes, directors are the worst at analysing their own films.

a. Shakespearean equivalents

17 For instance, Pinoteau sees Vic’s best friend (Pénélope) as a confidante in La Boum, which would make her a Shakespearean character of sorts:

18 Nonetheless, Penelope’s role in the film cannot legitimately be interpreted as “Vic’s confidante” – she is more of a sidekick and functions as comic relief, the “less-attractive-best-friend” to put it bluntly. In reality, it is the character of the great-grandmother (Poupette) who clearly channels the role of the Shakespearean confidante. Indeed, she takes on the characteristics of Juliet’s nurse. Juliet and Vic are the same age, and in both narratives, the old women (the nurse is referred to in the play as an “ancient lady” [II.3.134] [13] with aching bones [II.4.26]) are the characters who help explicit how old the young girls are. In Romeo and Juliet, the nurse explains:

Even or odd, of all days in the year,

Come Lammas Eve at night shall she be fourteen.

Susan and she – God rest all Christian souls! –

Were of an age. Well, Susan is with God;

She was too good for me. But, as I said,

On Lammas Eve at night shall she be fourteen,

(Romeo and Juliet, I.3.18-23)

19 Poupette is pictured as a similarly eccentric quick-witted woman who is not known for biting her tongue:

The allusions to Vic’s age (13 going on 14) are actually so numerous [14] that they seem to foreshadow, announce and build momentum towards the Shakespearean allusion to Juliet in the film, which also occurs in a scene between Vic and her great-grandmother. But surprisingly, when Vic mentions Juliet at last, she gets her age wrong:

20 However, the parallel between Poupette and the nurse is still worth investigating: in that scene, Poupette mentions 3-year-old Vic, echoing 3-year-old Juliet in the nurse’s monologue. The nurse famously recalls the time when Juliet was weaned (11 years before the beginning of the play, that is, around the time when Juliet turned 3, since she is “now” turning fourteen): the nurse’s late husband told Juliet, who had just fallen on her face, that she would later fall on her back when she is of (sexual) age. Poupette claims that she never talked to Vic as though she were three – implying that she did not talk to her appropriately even when the girl really was three years of age. The nurse’s husband, similarly, does not speak adequately to a 3-year-old. Interestingly, although Poupette provides Vic with an alibi to see her loved one (just like the nurse with Juliet), she is also, quite contrary to her Shakespearean counterpart, the guardian of Vic’s virginity – [15] in the previous scene as in the following:

21 The fact that Poupette is identified as the guardian of the young heroin’s virginity is actually key to understanding that La Boum is a modernized version of Romeo and Juliet “gone right”, i.e. endowed with a happy ending. Although Matthieu/Romeo and Vic/Juliet experience a simulacrum of a wedding night when she joins him in Cabourg, they do not have sex. They only spend the night together, in each other’s arms.

They fight, eventually, and Vic comes back to her grandmother (who was waiting for her in a room of the Cabourg Grand Hôtel) and allusively indicates that she is still a virgin:

22 La Boum and La Boum 2 are happy ending cautionary tales which explain to young girls that they should not lose their virginity to the first boy they fall in love with. [16] Romeo and Juliet on the other end is definitely a tragedy of bad timing. It is precisely because Vic does not rush into things that she finally realizes how fleeting and transient feelings of love can be: by the end of the film, she neglects Matthieu during the very party/boum she organized for her 14th birthday to dance with another boy, while the credits start rolling. [17] What would have become of Romeo and Juliet, had they been less hurried…? They might have fallen out of love just as quickly.

23 Although I recalled a few lines earlier that I intended to “read the film” regardless of what the director and scriptwriter might have to say about it (the author being “dead”), I need to add that Pinoteau explicitly stated that a literary quotation in a film was never accidental. Oddly enough, the German version of the film features an extra reference to the Bard:

In the French version, Vic does not recite “To be or not to be” but Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” for her German teacher: [18]

Pinoteau sees the substitution as unfortunate as the German poem is supposed to convey Vic’s ecstatic feelings, for which Hamlet’s dark mood does not constitute a good equivalent:

24 Another collateral damage of the translation is that Vic is pictured in the French scene as a “dunce” who has exceptionally done her homework and learnt her lesson, when she remains, in German, a student who could still “do better”. Schiller’s quotation was selected to illustrate the character’s state of mind at this precise moment in the story – to demonstrate her growing infatuation with her first boyfriend.

Matthieu and Vic had met during a party (the boum from the title), which strengthens their Romeo and Juliet quality. The following scene is typical of the way Romeo and Juliet are traditionally singled out during the ball, in stage or screen adaptations of the play. We may think of Tony and Maria’s blurred surroundings in West Side Story (Robert Wise, 1961), or, decades later, of Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes meeting through a fish tank, to the sound of Des’ree’s song “Kissing You”, in Baz Lurhman’s Romeo + Juliet (1996). Vic and Matthieu’s famous slow dancing is an avatar of Romeo and Juliet’s meeting scene:

25 The scene has become iconic in French pop culture. The identification to the legendary couple goes a step further when Vic Beretton’s parents express their disapproval of this particular relationship [19] in a context that subtly hints at social class differences: François Beretton is a dentist and Françoise Beretton, a cartoonist, whereas Matthieu’s parents, who remain nameless and almost faceless, work in the catering business. Poupette looks rather alarmed when she learns that Matthieu’s father is a pastry cook. Poupette and Vic stay at the Cabourg Grand Hôtel while Matthieu is doing an internship there, servicing their room. The difference of milieu reads as a social transposition of Romeo and Juliet’s family feud. However, we should see past the mere superimposition and pairing of characters (Poupette/nurse, Matthieu/Romeo and Victoire/Juliet) and consider the structure of the film.

b. La Boum’s Festive World: the party as carnivalesque green world

26 The question to be asked, then, is whether the Shakespearean reference permeates the entire architecture of the film. For instance, in Danièle Thompson’s Décalage Horaire (a 2002 screwball comedy starring Juliette Binoche and Jean Reno, which does not quote Shakespeare once), Mary Harrod identifies the setting where the protagonists meet as the Shakespearean green world of romantic comedy:

Thompson frequently makes reference to and borrows from an Anglo-Saxon tradition in the service of constructing romance. La Bûche echoes various rom-coms, notably written by Nora Ephron (When Harry Met Sally… [Bob Reiner, 1989] and Sleepless in Seattle [Nora Ephron, 1993], in exploiting the sense of time outside the everyday afforded by festive holidays, setting its action over the Christmas period. More originally, Décalage Horaire updates the otherness of the ‘green world’ of Shakespearean romantic comedy and its film descendants by reimagining such a realm in the liminal space of an airport. [20]

27 Using this particular terminology may be daring but it helps broaden perspectives. In Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye identifies the “green world” as a world of romance, a place of conversion towards the resolution of the play, the triumph of life over death, of the Pastoral over the wasteland, of spring over winter. [21] The green world is a “liminal space where social conventions are temporarily suspended, allowing stymied elements of a plot to play out and resolve themselves before a return to normalcy.” [22] François Laroque developed this concept in his study of seasons and calendar(s) within Shakespeare’s festive world, [23] after Mikhail Bakhtin’s seminal work on Rabelais. [24] In that respect, La Boum could be read as a festive comedy, with the party at its core. [25] Everything in the story converges towards that particular event which constitutes the knot into which the action ties itself, and from which other events stem naturally, until the denouement of Vic’s own boum – her 14th birthday party.

28 The film offers a timeline that is clear as crystal and reads as an almanac punctuated by several highlights in the year (mostly outings, parties and holiday breaks): [26]

- September 1979: Vic’s family moves to the 5th arrondissement of Paris (21 rue Valette) next to her new school (Lycée Henri IV).

- Time then quickly flies through Michaelmas term until Christmas thanks to a fast-paced edited instrumental sequence: video clip 13

- The party / la boum (February 1980)

- 1980 February holidays: video clip 14

- Spring / Easter holidays: video clip 15

- Whit / Pentecost (trip to Brussels which transforms into trip to Cabourg) May 1980: video clip 16

- End of the school year – Vic’s 14th birthday – July 1980. Interestingly, Juliet’s birthday is on July 31st (Lammas Eve).

29 All the events concerning the kids that take place outside the “ordinary time” of school and family have features of the carnivalesque: toppled hierarchy, inversion(s) or potential charivari.

Screwball comedy’s emphasis on private conversation transforms the function of the green world. According to Frye, most Shakespearean comedies involve a ‘rhythmic movement from normal world to green world and back again’, enabling the renewal of society. The normal world is characterized as a world of irrational law and parental tyranny, while the green world functions as a festive ‘holiday’ space in which social convention can be flouted. [27]

Let us go through a few examples and begin with the party itself: Raoul, who organized the boum, runs into his parents in the kitchen while the festivities are underway. Scared that his folks might be seen by his guests, he scolds them into bed – thus clearly inverting their ordinary rapport: he becomes, for the time of the party/festival, the authoritative figure of the place.

30 The party becomes an adult-free space where usual laws are naturally reconsidered – the teenagers smoke, flirt, invert common rules (one example being “le quart d’heure américain”, literally, the “American 15 minutes”, the French expression for “ladies’ choice” – a dance term which indicates that girls can choose their partners). Both concepts of carnival and green world make it possible for boys and girls to discard their identity. When Vic phones her parents because the boum bores her to death, Matthieu catches a glimpse of her for the first time and eavesdrops. She sees him do so, and because she does not want to come off as who she really is (a spoiled brat who calls daddy whenever she needs him), she keeps talking after her father has hung up, pretending the conversation is still going on. She adds that “they” (whoever “they” might be) will then crash another party, and finally have a drink at “La Main Jaune” (the “Yellow Hand”, a famous Parisian disco in the early 80s). She reinvents her identity, presenting herself as more emancipated and fashionable than she really is. The theory that identities were blurred during the boum (which hesitates between green world and carnival) is corroborated by the fact that Matthieu does not seem to recognize Vic (or to feel the same way about her) in the “normal” world of school:

31 Another sequence in the film qualifies as “mock carnival”. This particular scene occurs after Vic has come back from her ski trip – that is, after Spring break. One night, Vic sneaks out of bed and leaves her home to go to “La Main Jaune” because Penelope has called her on the phone, warning her that Matthieu went to the disco with another girl. Vic’s father manages to know where Vic is and joins the party:

Vic turns the situation to her advantage and seizes the opportunity to make Matthieu jealous by pretending that her father is a boyfriend of hers, creating a mock-charivari. The ploy of mistaken identities is as Shakespearean as can be. The event, occurring in the reimagined green world of romantic comedy (recreated through systematically dimly lit places – a party in a living room, a cinema house or a disco) will trigger Vic and Matthieu’s reconciliation in the normal world.

Conclusion: La Boum’s afterlives

Against the far wall, there was an ancient television that only played VHS cassette tapes propped up on a credenza, inside of which lay a veritable trove of bad taste: Crocodile Dundee, Mannequin, Adventures in Babysitting, and of course, the film that laid the ground rules for all French romantic comedies with sound tracks featuring a synthesized guitar, Sophie Marceau’s big breakthrough, La Boum. [28]

32 I hope the present essay manages to demonstrate that La Boum was indeed “the film that laid the ground rules for all French romantic comedies,” but does not belong to a “trove of bad taste.” Almost 40 years after it was released, the film has, on the contrary, stood the test of time, probably because it captured the Zeitgeist of the early 80s.

The notion that a somewhat Shakespearean structure has filtered through the many sieves of script writing is appealing. I am not suggesting that Pinoteau and Thompson deliberately wrote a festive comedy punctuated by seasons, calendars and celebrations with the concept of green world in mind. I agree that it is highly unlikely. Rather, it happened unbeknownst to them, because they imported an American matrix that was deeply steeped in Shakespeareanity. But Thompson did not merely appropriate the codes of romantic comedy: she was instrumental in shaping them.

33 If, as I have tried to suggest, it is appropriate to consider that a film can summon Shakespeare not only through quotations or storylines, but also in a more structural way, we do have our work cut out for us, because it is a rather inclusive approach, which would expand our potential corpus drastically.

What I would also like to come back to is the idea that what a director says about their film should often be taken with a pinch of salt. In a way similar to Claude Pinoteau’s when he (mistakenly in my opinion) sees a Shakespearean confidante in Penelope’s character, Lisa Azuelos identifies one of her shots as “Shakespearean” in her film LOL – the unofficial sequel to the first two Boum: [29]

34 I must confess that I am not convinced. All things considered, if there is a Shakespearean scene in the film, it is rather the one when Lola mistakenly assumes that her boyfriend (Maël) is having sex in the toilet with another girl, when she actually eavesdrops on an entirely different couple’s heated intercourse. Maël could be seen as an avatar of Hero in Much Ado About Nothing, Lola being Claudio in that scenario. Azuelos is undoubtedly fascinated with Shakespearean intertexts as her second romantic comedy featuring Sophie Marceau (Une rencontre, 2014) [30] weaves Romeo and Juliet into the narrative:

Unfortunately, we have got only so much time (and space) and this musical, literary and cinematographic reference will have to be the object of another essay.

Notes

1. Leger Grindon. The Hollywood Romantic Comedy: Conventions, History, Controversies. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2011, p. 1.

2. URL: https://www.hypable.com/shakespeare-crafted-the-genre-of-the-romantic-comedy/ (accessed 23 March 2021).

3. Œuvres Complètes. Paris: Bouquins – Robert Laffont, 2000, p 363.

4. See Kenneth Muir. The Sources of Shakespeare’s Plays. London: Methuen, 1977, chapter 19. See also Geoffrey Bullough. Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. Vol. 2. London: Routledge and Paul, 1958, pp. 61-139.

5. René Girard. A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 80ff.

6. See Stanley Cavell. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981.

7. URL: http://www.thecinessential.com/it-happened-one-night/modern-romantic-comedy (accessed 23 March 2021).

8. When Harry Met Sally is traditionally viewed by critics as the Renaissance of the American romantic comedy. See Douglas Williams. “Introspective laughter: Nora Ephron and the American comedy Renaissance.” In Gregg Rickman (ed.). The Film Comedy Reader. New York: Limelight Press, 2001, pp. 341-62.

The critical doxa sees Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) as a formula that was successfully reprised in Reiner’s film, launching the so-called renaissance of the genre: “[W]hen romantic comedy would begin its own mini-renaissance late in the 1980s, Allen’s influence would be ever present. More specifically, Rob Reiner’s Allen-ish When Harry Met Sally… (1989) kicked off a wave of quality romantic comedies that continues unabated to this very day” (Wes D. Gehring. Romantic vs. Screwball Comedy: Charting the Difference. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2002, p. 25).

“Accounts of the development of the romantic comedy often seem to compress the time between Annie Hall in 1977 and When Harry Met Sally in 1989 (Krutnik, 1998) telescoping the twelve years between them into a single impulse begun by Allen’s film and adopted by Nora Ephron, writer of When Harry Met Sally and writer-director of Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve got Mail. The particular brand of romantic comedies grouped together is New-York based, literate, self-reflexive, and may thus appear at first fairly homogenous. However, […] Allen’s film differs from the others in the complexity of its structure and radical ending” (Tamar Jeffers McDonald. Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. London & New York: Wallflower Press, 2007, p. 85).

9. URL: http://www.lefigaro.fr/cinema/2012/06/27/03002-20120627ARTFIG00498-daniele-thompson-nora-ephron-une-femme-drole.php (accessed 23 March 2021).

10. “Thompson’s embracing of certain conventions of genre cinema in much of her work can be interpreted as a feminist statement by an artist working against a backdrop of male-dominated French “high” cinephilic culture”; “Thompson’s unapologetic deployment of generic conventions helps to explain her exclusion from auteur status in her home country. […] These are all genres that have been associated with female artists and consumers – an impulse that has frequently gone hand in hand with their marginalization as ‘frivolous’” (Jill Nelmes and Jule Selbo (eds). Women Screenwriters: An International Guide. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, p. 347-49).

11. A role also portrayed by Marlène Jobert in the 70s in Les Mariés de l’an II (Jean-Paul Rappeneau, 1971), La Poudre d’escampette (Philippe de Broca, 1971) or Julie pot de colle (Philippe de Broca, 1977).

12. Roland Barthes. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Richard Howard. Aspen Magazine 5/6 (1967): 11.

13. For all the references to Shakespeare’s plays in this article: The Oxford Shakespeare – The Complete Works (second edition). Ed. John Jowett, William Montgomery, Gary Taylor & Stanley Wells. Oxford: Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, 2005.

14. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkD_l0yE-34&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021).

15. Poupette is, like the nurse, a bawdy character in the film, but she both deplores the virginity of one of her 26-year-old harp student and the promiscuity of pre-teens: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YXfz-BFQxWQ&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIa5AfQn730&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021).

16. Two excerpts from La Boum 2 to corroborate this point: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDXSuTlfl0I&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jT2M1jqM1LY&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021).

17. Incidentally, I do not think that the fact that Vic does not go steady with her Romeo by the end of the film makes it less of a romantic comedy. It cannot be questioned that La Boum 2 belongs to the exact same genre as La Boum, but at the end of La Boum 2, Vic and her boyfriend do hug and kiss on a railway platform. There is actually a kind of mirror effect between the two films: in the first film, the parents get back together while Vic is about to start a new fling. In the sequel, Vic’s relationship is likely to last a bit, whereas her parents’ future together is more uncertain. Romantic comedy cannot be reduced to a formulaic happy end. As Katherine Glitre points out: “Genre development is better understood as a dynamic process, rather than a linear evolution of a stable type. While genre recognition undoubtedly depends upon the repetition of easily comprehended conventions, mere repetition is pointless (negating the need for more than one text). Each new genre text will repeat some elements which will in turn become conventionalised. ‘In this way the elements and conventions of a genre are always in play rather than being simply replayed’ (Neale 1995: 170). Thus, genre operates in (at least) two temporal dimensions: there must be a synchronic sense of continuity, produced by the repetition of conventions; but there must also be a diachronic sense of change, produced by history” (Hollywood Romantic Comedy: States of the Union, 1934-1965. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006, p. 11).

18. Friedrich Schiller. “An die Freude”: “Seid umschlungen, Millionen! / Diesen Kuß der ganzen Welt!” (Be embraced, Millions! / This kiss to all the world!).

19. Vic’s mother blaming Matthieu for the way he drives his moped: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogj-FqaL1VA&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021); or Vic’s father street fighting with Matthieu: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vp5ezQClXhU&feature=youtu.be (accessed 23 March 2021).

20. Jill Nelmes and Jule Selbo (eds). Women Screenwriters, p. 349.

21. Northrop Frye. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

22. Adam Engel. Between Two Worlds: The Functions of Liminal Space in Twentieth-Century Literature. Dissertation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Graduate School, 2017. Online: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/j098zb36v (accessed 23 March 2021).

23. François Laroque. Shakespeare’s Festive World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993; “‘Old custom’. Shakespeare’s ambivalent anthropology.” Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 33 (2015). Online 2015: http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/2961 (accessed 23 March 2021).

24. Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich Bakhtin. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University, [1965] 2009.

25. “Shakespeare was creatively playing with both the Menander and Roman traditions of romantic comedy. But he was infusing these sources with a rich British festive tradition of “the green world”: country carnivals, folklore, songs, dances, customs, tales, and humour” (Andrew Horton. Laughing Out Loud: Writing the Comedy-Centered Screenplay. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, p. 52).

26. The school year calendar for 1979-1980 can be found here: https://cache.media.education.gouv.fr/file/86/4/5864.pdf (accessed 23 March 2021).

27. Kathrina Glitre. Hollywood Romantic Comedy, p. 73.

28. Courtney Maum. I Am Having So Much Fun Here Without You: A Novel. New York: Touchstone, 2014, p. 208.

29. “« LOL », faut-il le rappeler, signifie « laughing out loud » (mort de rire) en langage SMS. C’est aussi le diminutif de Lola, comme Vic était celui de Victoire dans La Boum, en 1980. Le film d’aujourd’hui revendique sa filiation avec celui d’hier: il n’aura échappé à personne que Sophie Marceau, ex-Vic de La Boum, joue aujourd’hui la maman de Lol. Mais le rapprochement bute sur le changement de société, voire de civilisation, survenu entre-temps. Car si La Boum préfigurait à sa manière les années Mitterrand et la bourgeoisie pré-bobo, LOL reflète un monde communément associé à Sarkozy. Les parents de Vic vivaient rive gauche (comme le président défunt), dans un confort sans ostentation. La mère séparée de LOL habite rive droite, dans le luxueux 16e arrondissement. L’escalier intérieur de son duplex a les dimensions des parties communes de beaucoup d’immeubles normaux. Lola est suréquipée en produits high-tech haut de gamme et fréquente un fils de ministre. Tourné avant la crise, le film a tranquillement entériné l’ère du paquet fiscal et constate sans état d’âme que les riches sont toujours plus riches” (Louis Guichard, Télérama 20/02/2009. Online: https://www.telerama.fr/cinema/de-la-boum-a-lol-la-mome-marceau-n-a-pas-change,39354.php (accessed 23 March 2021)).

30. For a description of the film Une rencontre, see my description on Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: http://shakscreen.org/films-description/101/ (accessed 23 March 2021).

Bibliography

- BAKHTIN, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University, [1965] 2009.

- BARTHES, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Richard Howard. Aspen Magazine 5/6 (1967). Online: https://www.ubu.com/aspen/aspen5and6/threeEssays.html#barthes.

- BULLOUGH, Geoffrey. Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. Vol. 2. London: Routledge and Paul, 1958.

- CAVELL, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- ENGEL, Adam. Between Two Worlds: The Functions of Liminal Space in Twentieth-Century Literature. Dissertation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Graduate School, 2017. Online: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/j098zb36v (accessed 23 March 2021).

- FRYE, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- GEHRING, Wes D. Romantic vs. Screwball Comedy: Charting the Difference. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2002.

- GIRARD, René. A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- GLITRE, Katherine. Hollywood Romantic Comedy: States of the Union, 1934-1965. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006.

- GRINDON, Leger. The Hollywood Romantic Comedy: Conventions, History, Controversies. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2011.

- HORTON, Andrew. Laughing Out Loud: Writing the Comedy-Centered Screenplay. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- JEFFERS McDONALD, Tamar. Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. London & New York: Wallflower Press, 2007.

- LAROQUE, François. Shakespeare’s Festive World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- ―. “‘Old custom’. Shakespeare’s ambivalent anthropology.” Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 33 (2015). Online 2015: http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/2961 (accessed 23 March 2021).

- MAUM, Courtney. I Am Having So Much Fun Here Without You: A Novel. New York: Touchstone, 2014.

- MUIR, Kenneth. The Sources of Shakespeare’s Plays. London: Methuen, 1977.

- NELMES, Jill and Jule Selbo (eds). Women Screenwriters: An International Guide. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- WILLIAMS, Douglas. “Introspective laughter: Nora Ephron and the American comedy Renaissance.” In Gregg Rickman (ed.). The Film Comedy Reader. New York: Limelight Press, 2001.

How to cite

DELORD, Frédéric. “When Shakespeare Met Romantic Comedies….” In Patricia Dorval & Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin (eds). Shakespeare on Screen in Francophonia: The Shakscreen Collection 5. Montpellier (France): IRCL, Université Paul-Valéry/Montpellier 3, 2021. Online: http://shakscreen.org/analysis/delord_2021/.

Contributed by Frédéric DELORD

<< back to top >>